How is Access To Medicines a Human Rights Issue?

What is access to medicines?

In 2015, the international community adopted the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), a set of 17 goals to be achieved by 2030. Goal 3—which committed to “ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages”—proposed a range of targets from addressing non-communicable diseases to substance abuse to environmental health. Imbedded in the fulfilment of Goal 3 was the target to end the epidemics of AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria, and neglected tropical diseases, and to combat hepatitis, water-borne diseases, and other communicable diseases. Goal 3 also called for the achievement of universal health coverage, greater investment in research and development of medicines for communicable and noncommunicable diseases, and as this chapter of the Health and Human Rights Resource Guide will discuss, the provision of access to affordable essential medicines.

What are essential medicines? By definition, essential medicines are those medicines that “satisfy the priority healthcare needs of the population,” and according to the World Health Organization (WHO), are selected on the basis of their estimated current and future public health relevance, evidence of efficacy and safety, and comparative cost-effectiveness. Medicines that meet these principles are published in the WHO’s model list of essential medicines, an inventory updated every two years and tailored to national or regional health needs in a national essential medicines list (EML). Countries can use national lists as a tool to prioritize their most pressing public health needs by focusing on public sector procurement and treatment of a limited and high-priority set of medicines.

Advances in scientific and technological innovation over the past several decades have changed the current picture of the world’s access to medicines. Innovation has motivated the development of new vaccines, reduced the prevalence of infectious diseases (for instance, polio and human papillomavirus),[1] and significantly decreased the global disease burden of HIV/AIDS. The invention of molecularly targeted therapies has even showed early promise for treating cancer, and the biomedical industry has made strides in strengthening the prevention, treatment, and control of transmissible and non-transmissible diseases.[2] Tuberculosis is illustrative of this progress: Between 1990 and 2013, the tuberculosis mortality rate fell by 45 percent, and the prevalence rate fell by 41 percent.[3]

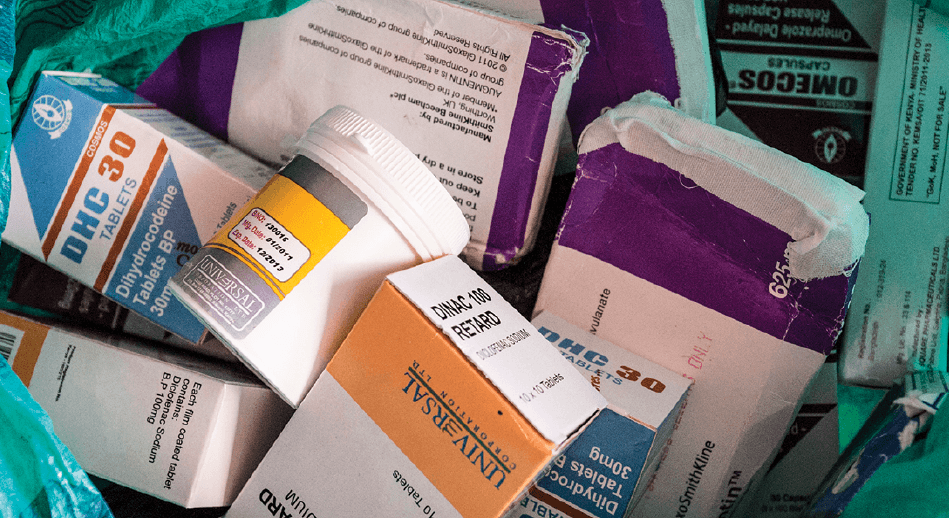

Despite notable progress, approximately 2 billion people around the world still face tremendous obstacles in accessing the medicines they need.[4] Moreover, the current research and development (R&D) model, which is largely market driven, is ill-equipped to address these gaps. It also should be noted that now more than ever, the high pricing of essential medicines is increasingly understood as a global problem affecting all countries, not just developing ones. While in the late nineties, the HIV/AIDS epidemic was the hallmark example of access problems, this picture has changed (prices of ARVs have come down to close to marginal cost of production in most countries, and at the end of 2014, 13.6 million people were able to access antiretroviral therapy[5],[6]), and the prevailing R&D model has us ill-prepared to respond to emerging infectious diseases such as Zika and Ebola; to neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) that predominantly affect populations with little purchasing power;[7] and to neglected populations, such as people living with rare diseases and children. The human rights-based approach put forth by this chapter will provide recommendations to resolve this incoherence between innovation and access by realigning global public health priorities and global health technology innovation.

This chapter intends to develop the current understanding of a human rights-based approach to access to medicines: it outlines the challenges that many populations face in accessing medicines (Section 1, part I), explains what understanding access to medicines through a human-rights based lens means (part II), summarizes human rights elements necessary for the realization of access to medicines (part III), and examines the tension between intellectual property (IP) rights and international human rights commitments (part IV). Part V focuses on key populations that encounter specific challenges within the broad landscape of enabling access to medicines, and Part VI recommends rights-based interventions and practices. After a tabular overview of the most relevant international and regional human rights standards related to the topic (Section 2), Section 3 discusses relevant human rights-based approaches to advocacy, litigation, and programming. Section 4 highlights specific country examples that have been successful in advancing the right to health and access to medicines for all, and the final section offers a glossary for further reading.

What are the issues and how are they human rights issues?

1. An overview of the international human rights framework

Access to essential medicines, nested in the right to the highest attainable standard of health, is well founded in international law. The 1946 Constitution of the World Health Organization and the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) both expressly recognize the right to health. The 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), which has 164 states parties, elaborates that the right to health includes “access to health facilities, goods, and services.” In General Comment 14 (2000) on the right to health, the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR) interprets the normative content of article 12 of the ICESCR.[8] Although the ICESCR only requires the progressive realization of the right to health in the context of limited resources, there is a core set of minimum obligations which are not subject to progressive realization, including access to essential medicines.[9] The WHO, numerous national court cases and resolutions of the Human Rights Council, and the Doha Declaration on TRIPS and Public Health reaffirm access to essential medicines as a human right that must be available “for all.”

While states hold the core responsibility for essential medicines provision, these responsibilities are shared with other non-state actors. For example, pharmaceutical companies have human rights responsibilities described by the former UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Health, including the duty to take all reasonable measures to make new medicines “as available as possible” for those in need.[10] Additionally, the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, which were unanimously endorsed by the UN Human Rights Council in 2011, obliges the private sector to take responsibility for violations of human rights related to access to medicines.[11] The international community also has human rights obligations to assist governments lacking resources to achieve their minimum core duties through international cooperation and assistance.[12] In the face of disaster, the international community bears the duty to contribute to relief and humanitarian assistance by providing medical supplies as a matter of priority.[13]

2. What does a human rights-based approach (HRBA) contribute to access to medicines?

What does a human rights-based approach (HRBA) contribute to access to medicines? A HRBA identifies all human beings as having indivisible, interrelated rights, and in this case, to health and to access essential medicines. In addition to duties and entitlements, and as articulated by the WHO[14] and CESCR,[15] a HRBA applies the principles of non-discrimination and equality; participation and inclusion; accountability; and the rule of law to universal access policies.[16] These principles are conceived to inform all stages of programming and advocacy work, including monitoring and evaluation. A HRBA to access to medicines draws special attention to marginalized, disadvantaged, and excluded populations and endows all populations with the ability to achieve outcomes through an inclusive, transparent, and responsive process.[17],[18]

A human rights-based approach can also be applied to improve access to medicines at the policy level. The right to health offers a framework from which national health policies and laws can be shaped for universal and equitable access. The result can manifest as positive health outcomes and the individual realization of health rights and access to medicines. For instance, domestic constitutions that recognize access to medicines as part of the right to health can support individual claims for essential medicines in national courts.[19] A good example of this is documented in the final section of this chapter, where the right to health ratified by the Kenyan Constitution played a role in supporting litigation that ultimately advanced access to ARVs for people living with and affected by HIV and AIDS.

For individuals and communities living in relative poverty, recasting their lack of access to health care and essential medicines not as a failure of government policy, but as a denial of their rights, is tremendously empowering. When the needs essential to a life lived in dignity are elevated to the rank of legal entitlements, they have the power to change political discourse and the horizon of social expectations.[20] Reframing health as a human right is not simply to appear in court; it is to expand the bounds of what is possible, to mobilize neglected communities, to raise public awareness and trigger activism and education.

Importantly, application of the human rights framework also provides a clear delineation of the spheres of responsibility of different stakeholders, as circumscribed by human rights treaties, guiding principles, and general comments. States are obliged under international human rights law to respect, protect, and fulfill the right to health, which includes an obligation to adopt legislative, administrative, and budgetary measures to facilitate access to medicines that are affordable, accessible, culturally acceptable, and of good quality.[21] This obligation for a state to “use all available resources at its disposal” [22] to satisfy its obligations with respect to health will often require a state to make full use of the public health flexibilities available under international law.[23]

Meanwhile, pharmaceutical companies bear a responsibility to respect human rights vis-à-vis the Ruggie trinity of protect, respect, and remedy.[24] Within this framework, corporations have a duty to (a) avoid causing or contributing to adverse human rights impacts through their own activities, and address such impacts when they occur; and (b) prevent or mitigate adverse human rights impacts that are directly linked to their operations, products, or services by their business relationships, even if they have not contributed to those impacts.[25] Essentially, pharmaceutical firms bear a responsibility to act with due diligence to avoid infringing on the right to health. These responsibilities come into stark relief when pharmaceutical firms prioritize the enforcement of their intellectual property rights at the expense of their right-to-health obligations.

3. Human rights elements for access to medicines

According to General Comment 14, realizing the right to access medicines is contingent upon the realization of four interrelated elements. Medicines must be (1) available, (2) accessible (with accessibility implying affordability, physical accessibility, and accessibility of information), (3) acceptable, and (4) of good quality.[26]

In complement to the “AAAQ” framework described above, WHO has outlined the following four key building blocks as essential toward ensuring access to medicines in national health systems:

-

Rational selection and use of essential medicines, based on national lists of essential medicines and treatment guidelines;

-

Affordable prices for governments, health care providers and individuals;

-

Fair and sustainable financing of essential medicines as part of the national health care system through adequate funding levels and equitable prepayments systems, to ensure that the poor are not disproportionately affected by medicine prices; and

-

Reliable health and supply systems to ensure sufficient and a locally appropriate combination of public and private service providers.”[27]

Article 2 (1) of the ICESCR also calls for the “progressive realization” of economic and social rights. In other words, the ICESCR recognizes that some states are burdened by resource constraints, and therefore, allows obligations to be realized over time. Therefore, in theory, a lack of resources can justify non-compliance. However, as it was just mentioned and as the Limburg Principles on the Implementation of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights have elaborated, the progressive realization of rights also suggests that states, regardless of their level of economic development, are obligated to take measures immediately and “move as expeditiously as possible” towards the realization of those rights.[28] Within the context of medicines, states must create and implement a reasonable action program to continuously improve access to essential medicines. State responsibility to provide essential medicines should be recognized in domestic law and given priority for public financing through sufficient budget allocation. Laws and policies within the health system (i.e. for universal health coverage or medicines pricing) and the broader legal order (i.e. for trade or intellectual property protection) should be aligned with achieving universal access to essential medicines. For instance, governments should make full use of the trade options under TRIPS flexibilities to safeguard access to essential medicines. (For an introduction on the TRIP Agreement and TRIPS flexibilities, see page 1-13.)

Regional instruments and documents agreed upon by the health community also clearly recognize the right to health. The African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (art. 16), the European Social Charter (art. 11), the Protocol of San Salvador (art. 10),[29] the WHO Constitution,[30] the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion,[31] and the Bangkok Charter for Health Promotion in a Globalized World[32] all consider health a fundamental human right.[33] These agreements can support access to medicines claims in domestic courts. In addition, the 1978 Declaration of Alma-Ata establishes a clear and important link between the provision of primary health care and the provision of essential drugs.[34]

International law gives clear guidance to states, and their implementation should be monitored in practice. Although more than 30 countries have not ratified the ICESCR, most states are party to at least one human rights instrument that recognizes the right to health. In terms of recognition in domestic law, 105 national constitutions include a degree of protection of the right to public health or medical care, while only 13 constitutions include the access to medicines as part of the right to health.[35],[36]

1. Intellectual property protection and trade

In addition to governments, non-state actors, such as pharmaceutical companies, have human rights responsibilities with respect to health. As explained by the UN Special Rapporteur on the right to health, Paul Hunt, pharmaceutical companies have the duty to take all reasonable steps to make a medicine “as accessible as possible” after it has been marketed, including to those who cannot afford (high) prices. These steps should be taken within a “viable business model.” [37] Paul Hunt contends that a company may be in breach of its responsibilities under the right to health “if a patent is worked without these steps being taken.”[38]

Even so, expanding economic globalization has tended to position the protection and enforcement of intellectual property (IP) rights at odds with international human rights law, and incoherencies have arisen between “patents” and “patients.” In 2015, the United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon recognized this tension when he established the UN High-Level Panel on Access to Medicines with a mandate to address the misalignment between the rights of inventors, international human rights law, trade rules, and public health. The culminating report posited that market-based models, which incentivize innovation, often lead to “insufficient investment… in R&D for diseases that predominantly affect the poor” and “prices charged by some right holders place severe burdens on health systems and individual patients, in wealthy and resource-constrained countries alike.”[39]

Among several recommendations, the report encouraged countries to reinforce the use of compulsory licenses through national laws, treat TRIPS flexibilities as a fundamental part of the TRIPS Agreement (not as an exception), and engage transparently in priority setting and coordination to prevent and stymie infectious diseases. (Compulsory licensing, the TRIPS Agreement.) It also encouraged the use of delinkage, a concept that refers to “delinking” the costs of R&D from the end prices of health technologies.

Patents

Pharmaceutical companies apply for patents for new, useful, and non-obvious inventions.[40] The public disclosure of an invention is rewarded with a twenty-year monopoly on its production, sale, and distribution. While pharmaceutical companies, and even governments, often claim that patents encourage innovation and provide crucial recuperation for research and development costs, the lack of transparency of R&D expenditure by the industry makes it almost impossible to determine the true costs of medicines.[41] Moreover, data has shown that the patent system tends to disproportionately benefit the holders of patent rights in developed countries at the cost of patients who consume technologies and goods in developing countries.[42],[43]

A patent confers so-called “negative rights” that allow the patent holder to exclude others from using his/her invention. Granted by the state, patents allow companies to control the production, distribution, use by others, and importation, and therefore, the price, of the product in question. Monopoly market power often leads to excessive prices and restricted access to affordable treatments for populations in developing and developed countries.[44],[45] Increasingly, new essential medicines are priced out-of-reach of patients in high-income countries as well.[46]

The purpose of the patent system is to incentivize innovation by giving the patentee exclusive monopoly rights over the use of the patented technology for a limited period of time, in return for disclosing valuable knowledge to society. The social gains derived from this system of protection must always be weighed against the inefficiencies resulting from monopoly market power and its vulnerability to abuse. Striking the optimal balance between innovation and access is extremely complex and inevitably influenced by the socioeconomic development agenda of the particular territory in which patent rights are enjoyed.

The patent regime’s vulnerability to abuse, particularly with respect to medicines treating for serious conditions – like hepatitis C or cancer – can be a matter of life or death.[47] As a UN expert consultant on access to medicines has written,

“While intellectual property rights have the important function of providing incentives for innovation, they can, in some cases, obstruct access by pushing up the price of medicines. The right to health requires a company that holds a patent on a lifesaving medicine to make use of all the arrangements at its disposal to render the medicine accessible to all.”[48]

The use of patent monopolies to limit generic competition compromises the “accessibility” (through affordability) of medicines, an issue that has been hotly debated in many countries. For example, in South Africa, the use of patents to block access to low-cost generic medicines have historically been responsible for high-priced essential medicines for HIV/AIDS and cancer, denying access to life-saving treatment for many. Similar strategies to challenge patent rights have been initiated in other developing countries. For example, in India, a patent application for Lopinavir/ritonavir (a treatment for HIV) manufactured by Abbott Laboratories (now AbbVie), was refused after I-MAK, a U.S.-based not-for-profit, filed a pre-grant opposition to it. I-MAK claimed that Abbott’s drug fell under Article 3(d) of the Indian patent law, which states “the mere discovery of a new form of a known substance which does not result in the enhancement of the known efficacy of that substance or the mere discovery of any new property or new use for a known substance or of the mere use of a known process, machine or apparatus unless such known process results in a new product or employs at least one new reactant.” I-MAK concluded that had Abbott secured a patent over a “new” formulation of Lopinavir/ritonavir, treatment for HIV/AIDS would have become out of reach for many. I-MAK’s litigation and advocacy work is highlighted in the best practices section (Section IV) of this chapter.

It is important to reverse the commonly held assumption that patent monopolies are the only means of recuperating the costs of, and therefore incentivizing, research and development for much-needed health technologies. While R&D is in fact needed to develop new drugs, a significant portion of this pivotal research is conducted with public financing. For example, advocates have pointed out that many antiretrovirals (anti-HIV drugs) were developed in public-funded laboratories.[49] Sofosbuvir, the high cost and highly effective drug for Hepatitis C, was also developed with public funding. Moreover, robust reports and analyses have also debunked the notion that patents are needed to recoup R&D costs.[50] A report by the Commission on Intellectual Property Rights, Innovation and Public Health finds, “…[W]here the market has very limited purchasing power, as is the case for diseases affecting millions of poor people in developing countries, patents are not a relevant factor or effective in stimulating R&D and bringing new products to market.”[51]

The introduction of the 1980 Bayh-Dole Act in the United States catalyzed significant research by allowing universities and public research institutions to patent the products of federally-funded research. However, limiting access to such discoveries through patent monopolies forces taxpayers to pay twice for the benefits of publicly-funded research.[52] The provision of public funding for research and development should instead be conditioned on strong, enforceable policies with respect to data sharing, open access publishing, non-exclusive licensing, participation in public sector patent pools, and affordability for low-income populations.[53]

Unfortunately, R&D shortfalls are most pronounced in developing countries where high-priority diseases are concentrated. Since pharmaceutical companies use patents to prevent competition, they are able to retain monopoly pricing on their drugs, making purchasing them nearly impossible for patients who—many lacking health insurance—must pay out of pocket for these life-saving medicines.[54]

The TRIPS Agreement

The Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) came into force in January 1995 in response to the growing need for multilateral cooperation on the regulation of intellectual property (IP). Developed by the World Trade Organization (WTO), the TRIPS Agreement globalized intellectual property requirements for the first time and marked a change in the way countries around the world interacted with the patent system. Prior to the establishment of TRIPS, intellectual property was regulated from country to country. Governments were able to tailor laws, policies, and practices to meet national priorities, and in some cases, excluded pharmaceuticals from patent protection altogether in order to safeguard the public’s health. Describing an age before the TRIPS Agreement, Ellen ‘T Hoen wrote, “The patenting of essential goods such as medicines and foods was long considered an act against the public interest.”[55]

New provisions embedded within TRIPS required WTO members to provide patents for all new, non-obvious, and useful inventions for at least 20 years (excluding the least developed countries and a few non-WTO Members, such as Somalia).[56]

Because patentability criteria are established by states and not by the WTO, states have significant discretion to define the parameters of patentability in a manner reflective of their domestic public health needs. For example, a developing country may decide to apply rigorous patentability criteria to ensure that generic firms are not unreasonably excluded from the market by incumbents who seek follow-on patents for new uses of known substances.[57] Striking the optimal balance between innovation and access will inevitably require a consideration of both public health needs and the domestic socio-economic landscape. Overly stringent patentability criteria also has the potential to discourage investment by foreign firms who fear that their intellectual property may not be adequately protected, thereby potentially jeopardizing economic development plans.

The DOHA Declaration

In November 2001 in Doha, Qatar, negotiations took place at the fourth WTO ministerial conference to address the TRIPS Agreement and the misalignment between profit-driven innovation models and public health. The result was the adoption of the Doha Declaration, a separate declaration on TRIPS and public health designed to respond to concerns about the implications of the TRIPS Agreement for access to medicines.

The declaration clarified that the TRIPS Agreement “does not and should not prevent member governments from acting to protect public health.” It also emphasized governments’ right to use TRIPS “flexibilities,” which are safeguards imbedded within the TRIPS Agreement that enable countries to adopt provisions to ameliorate the impact of patents on their population’s public health. Acknowledging “the seriousness of the concerns expressed by the least-developed countries (LDCs),” the declaration allowed these countries not to grant or enforce pharmaceutical product patents until at least 2016.[58] Paragraph 4 powerfully states, “[W]hile reiterating our commitment to the TRIPS Agreement, we affirm that the Agreement can and should be interpreted and implemented in a manner supportive of WTO Members’ right to protect public health and, in particular, to promote access to medicines for all.”[59]

To ensure strong IPR protection does not impede access to essential medicines, the declaration clarifies the scope of certain safeguards for all WTO members, which are embodied within the TRIPS Agreement. For instance, the declaration clarified that countries can determine the grounds upon which they issue compulsory licences for the generic manufacture of patented drugs.[60] The Doha Declaration also recognized the rights of governments to choose their own regime for parallel importation. Parallel imports are authentic products sold under intellectual property protection (copyright, patent, or trademark) in one country and shipped to another country without the manufacturer’s permission.[61] In the pharmaceutical context, parallel imports are genuine goods produced under patent, placed into circulation in one geographic market, and then imported into a second geographical market without the patentee’s authorization.[62] The legality of parallel imports depends on the choice of territorial exhaustion of the patent holder’s rights: national exhaustion means that rights are exhausted upon first sale within a nation but patent owners may prohibit parallel imports from abroad; regional exhaustion permits parallel imports among member countries (for example, within the European Union) but not from outside the region; and international exhaustion permits parallel imports from anywhere in the world as the patent holder’s rights are considered to be exhausted upon first sale in any country.[63] Typically, parallel importation is utilized to obtain drugs at their lowest price by exploiting price differences between markets. The Doha Declaration affirmed that countries are free to establish their own regime for parallel importation without challenge.[64]

Finally, the Doha Declaration waived the obligation of least developed country members (LDCs) to provide patent protection for pharmaceutical inventions until January 1, 2016, a deadline which has now been extended to January 1, 2033.[65] LDCs are also not required to provide patent protection to any invention at all until July 1, 2021, or until such a date on which they cease to be a least developed country member, whichever date is earlier.[66]

The Doha Declaration clarified that priorities under international trade law and international human rights law should be conversant with one another.[67] However, the promise of the Doha Declaration, which sought to protect the public’s health, has recently come under threat as states engaged in trade negotiations are pressured by governments and pharmaceutical companies alike to adopt even stricter conditions in their patent laws. These conditions are known as “TRIPS-plus” provisions because they require stricter protection of intellectual property than is required by the TRIPS Agreement. (Stricter conditions put binding obligations on countries to implement certain IP provisions beyond what is required by TRIPS.) Included among these strategies are preventing generic producers from using clinical data from the patented medicine to enter the market (data exclusivity),[68] and so-called patent “evergreening,” the practice of applying for multiple, successive patents on minor or insignificant variants or indications of already-patented compounds to extend the period of market exclusivity. While individual countries are free to implement strict patentability criteria that would prevent or limit evergreening, TRIPS-plus provisions, such as the obligation to grant patents for second medical use, would further facilitate the patenting of non-genuine innovations, or “evergreening.” Both processes extend companies’ monopolies, often prolonging high prices on medicines. An example of an attempt to “evergreen,” employed by Abbott Laboratories, is highlighted in Section 4 of this chapter. I-MAK filed a pre-grant opposition in response, as a result of which the patent was not granted. The UN Secretary-General’s High Level Panel on Access to Medicines explicitly recommended that WTO members make full use of the policy space available in TRIPS Article 27 by adopting and applying rigorous definitions of invention and patentability to curtail evergreening and ensure that patents are awarded only for genuine innovations.[69]

Although the Doha Declaration encouraged greater use of the public health flexibilities available under TRIPS, some countries have been unable or unwilling to make greater use of them. To address this failing, several public interest organizations – CEHURD in Uganda is one example – have intervened. In a policy brief, CEHURD encouraged the Ugandan government to maximize public health benefits from the new IPR protection regime by “making the most” of all flexibilities within TRIPS and adopting only the minimum levels of IPR protection that the agreement requires. A case study outlining this work is highlighted at the end of this chapter (Section 4). Additionally, international and multilateral institutions, including the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), WHO, UNITAID, and the Global Fund, have strongly supported and encouraged the use of TRIPS flexibilities. For instance, in 2016, UNITAID adopted a resolution on the use of the intellectual property flexibilities enshrined in the global trading system allowing developing countries to facilitate access to affordable medicines.[70]

In addition, free trade agreements (FTAs) and investment treaties between states seek to build even stricter IP regimes that exceed the minimum provisions in the TRIPS Agreement through the inclusion of TRIPS-plus provisions.[71] The United States, a principal exporter of intellectual property, has negotiated FTA agreements with Thailand, South Korea, Singapore and many other governments to increase the longevity of protection on patented drugs.[72] TRIPS-plus provisions threaten to overshadow the utilization of public health safeguards to protect public health by, inter alia, requiring patents for new uses of known substances, prohibiting pre-grant opposition, imposing data exclusivity periods, extending patent terms beyond twenty years for regulatory or marketing delays, and imposing restrictions on compulsory licensing and parallel imports.[73],[74] The 2009 Report of the Special Rapporteur on the right to health, Anand Grover, explicitly cautioned against the inclusion of TRIPS-plus provisions in international trade and investment treaties, emphasizing that such agreements “have had an adverse impact on prices and availability of medicines, making it difficult for countries to comply with their obligations to respect, protect, and fulfil the right to health.”[75] The Special Rapporteur recommended that developing countries and LDCs “not introduce TRIPS-plus standards in their national laws” and that developed countries “not encourage developing countries and LDCs to enter into TRIPS-plus FTAs and … be mindful of actions which may infringe upon the right to health.”[76] The UN Secretary General’s High-Level Panel on Access to Medicines echoed these calls, recommending that “[g]overnments engaged in bilateral and regional trade and investment treaties should ensure that these agreements do not include provisions that interfere with their obligations to fulfil the right to health” and that governments conduct public health impact assessments prior to entering into such agreements.[77]

Research and Development

The current innovation model primarily relies on market monopolies and high prices to fund research and develop new medicines. Describing the “prevailing model,” the aforementioned UNHLP report summarized: “[T]he biomedical industry, with the help of well-established intellectual property protection mechanisms, test data exclusivity, and significant public funding of research, invests in R&D, obtains marketing approval and pays for related expenses by charging prices that allow them to recover these substantial costs and generate a profit. Shareholders who invest in biomedical companies do so with the expectation of generating a return on investment.”[78] This model results in several perverse incentives for R&D and prioritizes the development of treatments for profitable diseases affecting the affluent while often neglecting the needs of the poor and marginalized who are unable to pay high end-product prices. The effects of the R&D model are also felt globally and regardless of socioeconomic status. For instance, antimicrobial resistance (AMR) represents a growing global health threat, and yet, since the development of effective antibiotics is both expensive and unprofitable, the market-driven R&D system has little incentive to respond. The existing drug development paradigm requires high levels of antibiotic use in order to recover the costs of R&D, but mitigating the spread of antimicrobial resistance demands just the opposite: severe restrictions on distribution and use.[79] As a result, R&D remains woefully inadequate and special intervention by governments, international organizations, the private sector, philanthropic organizations, and civil society are needed.[80] It is estimated that by 2050, failing to tackle AMR may cost 10 million premature deaths per year and $100 trillion in cumulative economic damage.[81]

The dearth of effective treatments for neglected tropical diseases is also a key example of the failings of the existing drug development paradigm. Buruli ulcer, for example, is a painful infection that affects over 30 countries. Combined antibiotics can treat the disease, but more innovative research is needed to develop an oral therapy to help scale-up effective disease control in poor settings.[82] In this way, a profit-driven R&D model runs counter to the right of everyone to the highest attainable standard of health. According to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), drug companies bear a responsibility to invest in research and development for neglected diseases through in-house R&D or support for external research.

Currently, the fear of damaging a medicine’s market share often discourages pharmaceutical companies from disseminating important information about new medicines. As a result, there is little transparency of research data and methods of drug development. This practice poses not only a health risk for medicines users, but it is also counterintuitive to the knowledge sharing and creative process needed to develop new drugs. Furthermore, limited information sharing effectively restricts oversight of drug research and knowledge exchange that will ultimately delay drug innovation. As stated in OHCHR’s Human Rights Guidelines for Pharmaceutical Companies, “The right to the highest attainable standard of health not only requires that existing medicines are accessible, but also that much-needed new medicines are developed as soon as possible. [emphasis added]”[83] In contrast to current practice, knowledge sharing is key to protecting patients from potentially harmful treatments and successfully developing new medicines.

Ultimately, the current model of innovation delivers inaccessible medicines at prices that have become unaffordable for low-, middle-, and high-income countries alike. The field of cancer care is one example of the need for effective and affordable treatments across the globe, including in low- and middle-income countries where cancer rates are on the rise.[84] A vial of trastuzumab (Herceptin®), a medicine for breast cancer recently added to the WHO Essential Medicines List, reportedly costs 15 times the per capita monthly income in India (2014);[85] meanwhile, it runs up to 50,000 UK pounds to treat one patient for a year (2012).[86] Some companies justify these exorbitant prices by asserting they are warranted by heavy research and development costs. However, this argument fails to consider the many breakthrough essential medicines that were developed with government (tax-based) funding and/or in public-funded laboratories.[87] In these cases where the fruits of drug development are patented and privately licensed, the public effectively pays twice: first to subsidize medical research, and again, to access the new medicine.

Contrary to the notion of the universality of the right to health, the CEO of pharmaceutical firm Bayer criticized India’s compulsory license for the cancer drug sorafenib (Nexavar®): “We did not develop this medicine for Indians. We developed it for Western patients who can afford it.”[88] This business model becomes all the more egregious considering “5 percent of global resources for cancer are spent in the developing world, yet these countries account for almost 80 percent of disability-adjusted years of life lost to cancer globally.”[89] Addressing this paradox, Paul Farmer, co-founder of Partners in Health, has observed, “The market fails when it comes to research and development of drugs for the poor.”[90]

Several innovative solutions for medicines R&D were tabled to the United Nations Secretary-General’s High Level Panel on Access to Medicines in 2016. The panel was tasked with assessing proposals to resolve the policy incoherencies between IP law and trade rules on the one hand, and human rights law and public health needs on the other.[91] Among the submissions they received was a proposal for an “Essential Medicines Patent Pool” that can allow for more affordable generics to be produced for communicable and non-communicable diseases while also remunerating patent holders.[92] Another recommendation was to initiate a global treaty on biomedical R&D to allow governments to collectively pool funding, coordinate, and monitor research in a way that delinks the price of new medical products from research and development costs, thereby improving the affordability of health technologies.[93] A radically new approach, “Health Innovation as a Public Good,” aims to “generate cheaper medicines for all public health needs” by shifting leadership, priority setting, and research financing to the public sector, which would result in public goods and eliminate the need for profit.[94] These and other proposals were considered before the High Level Panel released its Final Report in September 2016.

The Final Report provided a combination of high-level and highly specific recommendations for reform. With respect to TRIPS, the High Level Panel (HLP) reiterated existing calls for greater use of the public health flexibilities available under TRIPS but went slightly further; it cautioned governments and the private sector to refrain from threats, tactics, or strategies designed to undermine the use of TRIPS flexibilities by developing nations and recommended that any instances of undue pressure be reported to the WTO Secretariat during the Trade Policy Review of Member States and be met with punitive measures.

With respect to research and development, the HLP recommended the negotiation of a binding R&D convention that would delink the costs of R&D from end product prices and redirect R&D to pressing public health needs, including neglected tropical diseases and antimicrobial resistance.

With respect to global health governance, accountability, and transparency, the HLP recommended that (a) Member States improve institutional coherence between trade, IP and public health at the national level; (b) an independent review body and an inter-agency task force be developed by the UN Secretary-General to assess progress on health technology innovation and access, and increase coherence between multilateral organizations, respectively; and (c) private biomedical companies report annually on actions taken to promote access to health technologies, and engage in transparent disclosure of the costs of R&D, marketing, and distribution, and any public funding received in the development of health technologies.

The many, varied recommendations of the High Level Panel illustrate the complex challenges produced by the interaction between intellectual property, international trade, international human rights, and public health. Importantly, they demonstrate that the incoherencies between these spheres of influence can only be resolved using robust accountability frameworks that hold all stakeholders responsible for the impact of their actions on access to affordable health technologies.[95]

2. Non-discrimination and equality

Access to medicines remains an illusory goal for traditionally marginalized groups. However, non-discrimination and equality – two of the most fundamental principles under human rights law – is central to the right to health.[96] Under the ICESCR, access to medicines should be realized without distinction on the grounds of race, color, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, disability, birth or other status.[97] The International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination also emphasizes that states must prohibit and eliminate racial discrimination in the enjoyment of public health and medical care.[98] Failure to comply with these standards amounts to a violation of international law.[99],[100]

However, non-discrimination and equality do not always imply equal treatment.[101] In some cases, states must assume positive obligations to prioritize underrepresented individuals and communities.[102] For example, certain populations face particular health challenges, including higher mortality rates or barriers to access, that must be reflected in national health policies.[103]

People living with HIV and AIDS[104]

Navi Pillay, former UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, has stated, “The face of HIV has always been the face of our failure to protect human rights.” HIV/AIDS is a global epidemic. More than 30 million people have died of AIDS, and there are approximately 36.9 million people living with HIV today.[105],[106] Each year, some 2.5 million people become infected with HIV, and around 1.7 million people die of AIDS-related causes, mostly in low- and middle-income countries.[107]

HIV/AIDS disproportionately affects people living in developing countries and persons living in poverty. This distribution is deeply rooted in social, economic, and gender inequalities. Sub-Saharan Africa remains the worst-affected region, with 69% of all persons living with HIV/AIDS.[108] The Caribbean region has the highest HIV prevalence outside of sub-Saharan Africa, and the number of new HIV infections is increasing in Eastern Europe, Central Asia, North Africa, the Middle East, and parts of Asia and the Pacific.[109]

HIV is treated with antiretroviral (ARV) therapy, which is a combination formula of at least three antiretroviral drugs that maximally suppress the HIV virus and halt the progression of the HIV disease.[110] ARV therapy is effective both as life-saving treatment and as protection against HIV/ AIDS. However, coverage for people living with HIV/AIDS remains unequal, and in 2011, just 54% of people indicated for ARV in low- and middle-income countries received the treatment. Globally, just 28% of children in need of treatment received ARV.[111]

Although there is not yet universal access in many countries, treatment has been successful in extending life expectancy, decreasing HIV transmission, and promoting community activism and empowerment around HIV/AIDS and the protection of human rights. According to the Global Commission on HIV and the Law, “Legal strategies, together with global advocacy and generic [drugs], resulted in a 22-fold increase in ART access between 2001 and 2010.” These legal strategies included framing lack of access to ARV as a breach of human rights. Civil society action, such as that of the Treatment Action Campaign in South Africa, held national governments accountable to their legal obligations in international law and their domestic constitutions These strategies can be replicated to access treatment for other epidemics.

A number of mechanisms are also available to help make HIV medicines more affordable. These include robust generic competition, local production, voluntary licensing by innovator to generic companies, and the use of flexibilities in the international trade and intellectual property rules (through the TRIPS Agreement and other WTO mechanisms) to achieve wider access to affordable generic medicines. One such flexibility is compulsory licensing, which is permitted by TRIPS Article 31. Under a compulsory license, the issuing government sets the terms upon which a third party can exploit a patented product without the patent holder’s consent. The patent holder receives adequate remuneration and retains exclusive rights over the patented good, except with respect to the compulsory licensee. Compulsory licenses have been an integral component of patent law for centuries, and have been used extensively by countries around the world.[112] Canada’s highly permissive compulsory licensing regime facilitated significant price reductions in pharmaceutical drugs,[113] and helped to establish a robust generic manufacturing industry before it was dismantled by NAFTA in the early 1990s.[114] Since the start of the 21st century, a number of developing countries have either issued or threatened to issue compulsory licences on pharmaceutical products to expand access to affordable medicines, including Thailand, Brazil, Rwanda, Indonesia, Malaysia, Zambia, Zimbabwe, and Mozambique.[115]

There are numerous advantages associated with compulsory licensing for pharmaceutical drugs, including, inter alia, the ability to achieve significant price reductions long before the expiry of the patent term; the reduction in dependence on a sole supplier; and the ability to respond swiftly to public health emergencies. In 2015, South Africa experienced severe shortages of Lopinavir/ritonavir (LPV/r), a combination antiretroviral medicine used in first-line ARV regimens for paediatric patients, and second-line regimens for adults and adolescents who have developed resistance to first-line treatments. The drug is marketed as “Aluvia” by patent holder AbbVie, which is the sole supplier in South Africa.[116] The shortages resulted from AbbVie’s inability to deliver adequate supplies, and resulted in significant treatment disruptions for HIV patients. Treatment disruptions place HIV patients at risk of developing drug resistance and immunological failure. Patients who develop resistance to second-line treatment must be switched to third-line treatment, which is six times more expensive.[117] Although generic versions of Aluvia were already prequalified by the World Health Organisation, they could not be produced in, or imported into, South Africa until the expiry of AbbVie’s patent in 2028.[118] The shortages triggered significant public outcry, and civil society organizations called for the South African government to issue a compulsory license on Aluvia.[119] No such license was issued. Cases like these have prompted widespread calls for governments to “adopt and implement legislation that facilitates the issuance of compulsory licenses. Such legislation must be designed to effectuate quick, fair, predictable, and implementable compulsory licenses for legitimate public health needs, and particularly with regards to essential medicines”.[120]

As countries continue to confront new challenges in the fight against HIV/AIDS, compulsory licensing will continue to be a critical tool for sustainable access to affordable antiretroviral treatment. Namibia, for example, has one of the highest antiretroviral treatment (ART) coverage rates in sub-Saharan Africa (at 90%) but the country is increasingly struggling to combat HIV drug resistance (HIVDR) which requires second-line ART regimens with long-term toxicity and higher annual costs. There are widespread concerns about the sustainability of Namibia’s ART program given its heavy reliance on donor funds. Accordingly, compulsory licensing is critically needed to maintain drug-supply continuity and facilitate the development of local pharmaceutical manufacturing capacity.

Children

Every year, over eight million children under five years of age die, many from illnesses such as diarrhea, malaria, HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and pneumonia.[121] Children and young people are also among the worst affected by the HIV epidemic, in large part due to mother-to-child transmission and slow progress in the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of HIV in children specifically. Due to interrelated biological and social reasons—contact with infected persons, being less than five years of age, and severe malnourishment—children are also especially vulnerable to TB. Each year, there are approximately 500,000 new TB cases and up to 70,000 TB deaths among children.[122]

As a particularly vulnerable, and often silent, subset of the population, children face unique challenges that prohibit them from enjoying the right to health, including access to child-friendly drugs. For instance, although effective treatments have been developed for many of the major diseases that affect children, often pediatric versions of these treatments do not exist. Children require dosages that are reflective of their age, physical condition, and body weight.[123] Though it is common for healthcare providers to split adult dosages into halves or quarters for children’s use, these makeshift tablets risk inaccurate dosing, thereby reducing the efficacy and/or safety of the treatment.[124]

Adult sized medicines are also often unpalatable and difficult to digest for children. Oral solutions and syrups are more tolerable, and yet medications in these forms are usually unavailable, too expensive, or unsuitable for use in low-income settings. For diseases requiring several treatments per day—HIV/AIDS is one example—a fixed dosage combination approach is ideal. However, these combination pills are much more expensive than their adult counterparts.[125] To address some of these gaps, pediatric ARV drug development projects have been initiated. Generic companies also have been able to develop formulations for children.

Prior to 2006, few strides had been made in the research and development of child-friendly medicines. The difficulty of administering clinical trials on children made advances even more difficult.[126] However, in 2006, civil society organizations and governments began to partner in a quest to develop safer and better quality medicines specifically tailored to a child’s unique needs.[127] Improvements have been slow but steady. For instance, in 2007 WHO launched a campaign to remove some of these barriers, publishing the WHO Model List for Essential Medicines for Children and launching a campaign to promote the use of child-friendly tablets.

Women

Women are particularly vulnerable to violations of their rights in seeking access to medicines, especially for sexual and reproductive health care services. For example, women in many developing countries face a shortage of prophylactic uterotonics, a drug that helps to prevent and treat Postpartum Haemorrhage (PPH). PPH, defined as a blood loss of 500 ml or more within 24 hours after birth, is the leading cause of maternal mortality globally.[128] Without access to prophylactic uterotonics during the third stage of labor, scores of women in low-income countries suffer from long-term disability, contract severe maternal conditions associated with substantial blood loss, and/or die preventable deaths. It is therefore unsurprising that the provision of essential medicines for sexual and reproductive health is a “core” duty of the state in the CESCR’s General Comment 22 on the right to sexual and reproductive health.[129]

Women and girls who have been trafficked for prostitution are especially vulnerable to HIV/AIDS and sexually transmitted infections and require access to medicines on a non-discriminatory basis. In its General Recommendation on “Women and Health,” the Committee to Eliminate Discrimination Against Women (“CEDAW”) noted:

“The issues of HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted diseases are central to the rights of women and adolescent girls to sexual health. Adolescent girls and women in many countries lack adequate access to information and services necessary to ensure sexual health. . . . States parties should ensure, without prejudice or discrimination, the right to sexual health information, education and services for all women and girls.”[130]

In some cases, discrimination against women in their pursuit of medicines can be blatant. For instance, as the chapter on patient care has noted, Human Rights Watch documented abuses committed by health personnel who had deliberately refused to give pain-relieving medication to women while in labor.[131]

The Special Rapporteur on the right to health states, “Stigma and discrimination against women from marginalized communities, including indigenous women, women with disabilities and women living with HIV/AIDS, have made women from these communities particularly vulnerable to such abuses.”[132] Female patients from marginalized populations have the right to seek health care, and goods that promote health (i.e. medicines), in a manner that is non-discriminatory and respects their dignity.

More recently, the Zika epidemic highlighted the systemic discrimination suffered by women in exercising their right to health. Laws and policies in Zika-affected countries which significantly curtail female reproductive rights thereby violate the right to health and the right to life enjoyed by both mother and child, given the proven link between Zika infection and microcephaly. The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein, has repeatedly called for the repeal of laws that restrict access to sexual and reproductive health services to ensure that women have the information, support and services they require to exercise their rights to determine whether and when they become pregnant.[133]

Prisoners/ detained persons

The right to health in prison lies at the nexus of positive and negative rights in the sense that, having deprived prisoners of their liberty and their ability to provide for their own health, states bear a positive obligation to protect their right to life and their right to health. Prisoners and detained persons in most countries do not relinquish their rights when they enter the jail system. However, since they are in many ways dependent upon the prison system, this population often faces violations of their rights, including the right to access medicines. [134]

Prison environments render their occupants more susceptible to certain diseases.

For example, although many prisoners living with HIV contracted their infections before imprisonment, the risk of infection while in prison is high due to high-risk sexual and other behaviors, like sharing needles. High-risk sexual behaviors, including unprotected sex and sexual violence, rape, and coercion, are common in prison and increase prisoners’ vulnerability to HIV. Unsafe drug injection, blood exchange, and the use of non-sterile needles/cutting instruments for tattooing are also common and increase HIV vulnerability. Poor prison conditions, including overcrowding, malnutrition, poor security, and lack of health facilities and staff, contribute to the spread of HIV and violate prisoners’ human rights.

Some prisons create separate or alternative sections for HIV-positive prisoners, segregating them from the rest of the prison population. In parts of Russia, prisoners are tested for HIV and those who test positive are imprisoned together, but separated from the general prison population. Two states in the United States, Alabama and South Carolina, continue to segregate prisoners living with HIV. The American Civil Liberties Union and the AIDS Project recently filed a lawsuit calling the practice discriminatory.[135] Their reports highlight additional human rights violations that are consequences of discriminatory segregation.[136]

In addition, prisoners are by definition not free individuals who can go to the pharmacy, and they are dependent on others to physically provide medicines. Prisoners also often have little or no means to finance medicines, so they must be funded by the prison system. Both of these obstacles routinely obstruct prisoners from realizing their right to access medicines. For instance, due to high costs, it has been documented that prison systems have withheld newer medications, including drugs for Hepatitis C, from patients in need. Several such cases have been documented in the United States, including in Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and Minnesota.[137]

The prison population includes vulnerable groups with special needs, including prisoners with mental health care needs, elderly prisoners, and prisoners with terminal illness. These vulnerable populations may require special attention to ensure that their rights to health and life with dignity are realized.

Older persons

Older persons are a vulnerable group and more susceptible to issues related to non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and pain management control. NCDs, such as cancer, heart disease, and diabetes, affect many people—but especially older people. NCDs prevention and treatment can also demand a chronic (and expensive) course of medicine that may not be available or affordable for this population.[138] Because government-funded medicines are often the only source of treatment for this population, many of these patients must pay out-of-pocket to access medicines for their chronic conditions. These sometimes catastrophic expenses can force older patients to have to choose between medicines they need and their financial stability.[139] The problem becomes even more acute when one considers the new, expensive medicines with proven therapeutic value to treat cancer. This raises an ethical and economic dilemma for industrialised and developing countries alike of how to afford these high-cost, therapeutically-innovative medicines.

In developing countries, the affordability and accessibility of chronic and/or expensive pharmaceuticals is especially limited, and in many cases, unaffordable medicines leave older people with pain control as the only viable treatment. However, opioids needed to control pain are subject to additional regulation that restricts their much-needed use. While the international drug control framework, which includes the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, the Convention on Psychotropic Substances, and the United Nations Convention on Illicit Traffic in Narcotic and Psychotropic Drugs, has been crafted to combat illicit drug markets, it is incoherent with obligations that derive from human rights law. The restrictive interpretation of the control mechanisms included in the international drug control treaties directly hinder states access to controlled substances for medical purposes.[140]

The United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights states that, with regard to the realization of the right to health of older persons, “attention and care for chronically and terminally ill persons [is important], sparing them avoidable pain and enabling them to die with dignity.” Therefore, an important component of palliative care is access to essential drugs that alleviate pain.

In 2007, the International Association for Hospice and Palliative Care (IAHPC), in collaboration with 26 palliative care organizations, developed a list of essential medicines for palliative care.[141] Of the 34 medications listed, just 14 were included in the WHO Model List (most recently updated in 2011), and morphine was the only strong opioid analgesic included. Oral morphine is particularly essential for palliative care because it provides an inexpensive option for pain management. However, especially in low- and middle- income countries, only opioid formulations that are more expensive or more difficult to use, such as injectable morphine, are available. The high cost of these opioids hinders access to treatment. Meanwhile, the low profit margin from oral morphine is exacerbated by additional costs of unnecessarily burdensome regulatory requirements, which may further deter the pharmaceutical industry from supplying it.[142]

Persons living with neglected diseases[143]

Neglected diseases are diseases for which there is a lack of sufficient medical innovation, resulting in inadequate, ineffective, or non-existent means to prevent, diagnose and treat them. The lack of sufficient medical innovation is often caused by a lack of market incentives to invest in products that will predominantly be directed towards populations with little or no purchasing power.[144] Examples include: leishmaniasis, schistosomiasis, onchocerciasis, lymphatic filariasis, Chagas disease, malaria, leprosy, African trypanosomiasis, tuberculosis and dengue.[145]

Neglected diseases are demonstrative of entrenched global inequities that perpetuate disparities in the enjoyment of the right to health between the rich and the poor. For example, although the situation has improved, drug development efforts have largely focused on diseases with a higher return than those that afflict predominantly poor populations.

Through international cooperation and research and development,[146] states bear the responsibility to improve the underlying determinants of health that predispose certain populations to these diseases.[147] More immediately, governments and civil society must pressure pharmaceutical companies to produce medicines that address neglected diseases. For example, the African Union Commission has suggested these activities should include “giving large pharmaceutical firms incentives to investigate the diseases that affect Africa, instead of focusing on the diseases of rich countries.”[148]

Neglected diseases do not only suffer from lack of R&D funding. The patenting of basic scientific research tools, such as gene fragments, does not allow developing world scientists to benefit from accumulated research. Publishers often price their copyright journals beyond the means of the Global South, wherein scientists are denied the right to information and developing countries subsequently do not benefit from the right to scientific progress and research.

What are rights-based interventions and practices in the area of access to medicines?

Operationalizing a human rights framework is an essential approach toward advancing access to medicines. This multi-pronged approach should involve participation and coordination between governments, philanthropic organizations, international entities, civil society groups, and the private sector.

To start, programmatic reforms to increase access must be incorporated in national policies and programs, with special consideration for populations that routinely face access barriers, such as incarcerated persons, women, children, and those affected by diseases that can only be treated with high priced medicines. Equally, the prioritization of access to essential medicines must be reflected in new rights-based laws and licensing the products of medical research. In addition, states, especially in the Global South, should fully utilize the public health flexibilities available under TRIPS to address their country’s specific domestic health needs. A number of other mechanisms are available to help make medicines more affordable. Some of these methods include promoting generic competition, local production, and voluntary licensing by innovator to generic companies. Pharmaceutical companies should respect the right of states to use TRIPS flexibilities and refrain from pursuing stronger intellectual property protection than that is required by TRIPS. Initiatives to increase access to medicines must also bear in mind the principle of transparency, so that accountability frameworks can hold all stakeholders to account and better address the misalignment between the right to health, trade, intellectual property, and public health objectives.[149]

A human rights approach must also be supported by robust international assistance and cooperation, especially where public health objectives cannot be fulfilled immediately by the state.[150] As part of the tripartite classification of obligations for all human rights, experts increasingly contend that the duty to fulfill rights suggests that developed countries have positive duties beyond borders.[151] According to the CESCR, developed countries have a responsibility to contribute to contribute to countries in need, to “the maximum of [their] capacities,” in situations of emergency.[152] The courts can also play an important role in enforcing the right to health. In fact, right-to-health litigation to advance access to medicines exemplifies, in very practical terms, how human rights can be used to force governments to act.

The strategies outlined below all strive to increase access to medicines for all. Some of these strategies are ongoing, and should continue or be scaled up.

Official and non-governmental initiatives and international assistance

The right to health obliges states to advance access to medicines through international assistance and cooperation.[153] To help meet these commitments, the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, an independent, multilateral financing entity, was conceived in 2002. The Global Fund directs resources to countries to support their response to HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria and is the largest multilateral funder program that provides access to treatments those diseases.[154] UNITAID, an international drug purchasing financing facility, has been another pioneering initiative. Through multilateral coordination and strategic market interventions, UNITAID creates and improves upon incentives for the pharmaceutical sector to better meet the world’s health needs.[155] Finally, the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, otherwise known as PEPFAR, is another health financing mechanism, which has been instrumental in curtailing the HIV/AIDS epidemic by supporting ART treatment for nearly 9.5 million people worldwide as of September 2015.[156]

This concept, which describes a financing model characterized by the uncoupling of R&D costs and consumer prices for health technologies, is known as “delinkage.”[157] A joint WTO, WIPO, WHO study described “delinkage” in the following terms: “One important concept that evolved from this discussion is the concept of delinking price of the final product from the costs of R&D. This concept is based on the fact that patents allow developers to recoup the costs and make profits by charging a price in excess of the costs of production. This way of financing R&D is viewed as constituting a barrier to access to medicines in countries where populations pay out of their own pockets for medicines and thus cannot afford to pay high prices. The principle of delinking is based on the premise that costs and risks associated with R&D should be rewarded, and incentives for R&D provided, other than through the price of the product.”[158]

As the world moves to curtail the spread of diseases beyond HIV/AIDS, primarily for diseases that are not incentivized by a robust market, innovation models should actively seek to “delink” R&D costs from the end price of products and share the burden of these costs on an international scale. As the 2016 UNHLP has stated, the current “patchwork” of public, private, and philanthropic funding is not sufficient enough to sustain long-term public health financing.[159] New proposals have included using the WHO as a galvanizing force to “initiate international talks about priority setting and burden sharing of the cost of essential health R7D and set new rules to allow for financing of innovation while equitable access to those innovations is assure. This would initiate international implementation of delinkage.”[160] A subsequent adoption of a new medical R&D framework could also include the following elements: “R&D priorities driven by health needs; Binding obligations of governments to invest in health R&D; Equitable distribution of contributions across countries; Measures to improve the regulatory environment and collaboration; Measure to ensure affordability of the end product; Access-maximising licensing practices to deal with IP issues; and Innovative approaches to incentivising R&D based on linkage principles.”[161]

Governance and flexibilities allowed under TRIPS

World Trade Organization (WTO) Members must make full use of TRIPS flexibilities to promote access to medicines. In accordance with Article 8 of the agreement, states may “adopt measures necessary to protect public health” as they “[formulate] or [amend] their laws and regulations.” States should also take advantage of “the policy space available in Article 27… by adopting and applying rigorous definitions of invention and patentability that are in the best interests of the public health of the country and its inhabitants.”

Flexibilities must be explicitly incorporated into national policies and legislation. In particular, laws should be amended to promote compulsory licensing, permit parallel importation, promote pre-grant opposition, strengthen antitrust remedies for abuse of monopoly power, and strengthen patentability criteria to ensure that patents are only awarded “when genuine innovation has occurred.”[162]

Pharmaceutical policy reform

As Ministers and senior public officials have suggested,[163] pharmaceutical companies can and should exercise good corporate governance. They can do so by adopting the OHCHR’s Human Rights Guidelines for Pharmaceutical Companies, including:

-

The company should adopt a human rights policy statement which expressly recognises the importance of human rights generally, and the right to the highest attainable standard of health in particular, in relation to the strategies, policies, programmes, projects and activities of the company;

-

The company should integrate human rights, including the right to the highest attainable standard of health, into the strategies, policies, programmes, projects and activities of the company;

-

The company should always comply with the national law of the State where it operates, as well as any relevant legislation of the State where it is domiciled;

-

The company should refrain from any conduct that will or may encourage a State to act in a way that is inconsistent with its obligations arising from national and international human rights law, including the right to the highest attainable standard of health.”[164]

Pharmaceutical companies are responsible for investing in research and development to benefit all patients. In the realm of competition and pricing, companies can engage in fair market practices.[165] For instance, in 2014, Gilead issued a voluntary license for sofosbuvir to generic producers, a treatment for Hepatitis C, which allows production and supply of generic SOF to 101 countries for this disease. Although this is a positive step for 101 nations, Gilead’s license still excludes countries where 73 million people with the Hepatitis C virus live. This move effectively leaves out 46% of HCV patients globally from an agreement that can deliver more affordable generic treatment and allows supply to other countries in the event that, for instance, a compulsory license is issued.[166]

Health systems strengthening

Access to medicines fundamentally depends upon well-functioning health systems. According to guidelines set out by the OHCHR, systems must be “integrated, responsive, and accessible.”[167] Governments should scale up their investment in these systems, as well as scale up transparency and participatory priority-setting for drug spending.

Governments should also erect strong regulatory systems to ensure medicines are safe, effective, and of assured quality. A well formulated and comprehensive National Medicines Policy (NMP), as laid out by WHO, can guide governments to set priorities for the national pharmaceutical sector that satisfy their human rights obligations.[168] A national essential medicines list outlines the most clinically- and cost-effective medicines for priority diseases. When used within a health system, a national essential medicines list can help limited drug budgets achieve the greatest public health impact. In line with the principle of progressive realization, governments should continuously increase the public funding available for essential pharmaceuticals, especially considering many of the most marginalized populations either pay out of pocket or make do without these medicines.

Claim health rights before domestic or regional courts

The courts can also play a role in promoting health rights, including addressing the affordability and accessibility of medicines.[169] This intervention in particular shows, in very practical terms, how human rights can be used as a tool to force the government to act.

The claims of individuals or groups have been particularly efficacious when access to medicines is linked to a country’s constitutional right to health or human rights treaties (including the right to health) ratified by the government. For example, a study identified that state recognition of the right to health in international or domestic law created a supportive environment for cases in which access to essential medicines was claimed as a derivative of the right to health and thereby reinforcing the enforceability through domestic courts.[170]

Two case studies at the end of this chapter, based in Kenya and Georgia respectively, highlight recent trends in litigation concerning access to medicines. Both examples indicate that support from non-governmental organizations can help shepherd the likelihood of success. Secondly, it might be inferred that judges are increasingly ruling in favor of the protection of patient’s rights over the enforcement of patents.[171]

Though an uptake in the amount of cases litigating the right to medicines in national courts has been documented, the extent that this movement has on the right to health as a whole has yet to be determined.[172],[173]

2. Which are the most relevant international and regional human rights standards related to access to medicines?

How to read the tables

Tables A and B provide an overview of relevant international and regional human rights instruments. They provide a quick reference to the rights instruments and refer you to the relevant articles of each listed human right or fundamental freedom that will be addressed in this chapter.

From Table 1 on, each table is dedicated to examining a human right or fundamental freedom in detail as it applies to patient care. The tables are organized as follows:

| Human right or fundamental freedom | |

| Examples of Human Rights Violations | |

|

Human rights standards

|

UN treaty body interpretation This section provides general comments issued by UN treaty bodies as well as recommendations issued to States parties to the human right treaty. These provide guidance on how the treaty bodies expect countries to implement the human rights standards listed on the left. |

| Human rights standards |

Case law This section lists case law from regional human rights courts as well as from the country level. Case law creates legal precedent that is binding upon the states under that court’s jurisdiction. Therefore it is important to know how the courts have interpreted the human rights standards as applied to a specific issue area. |

|

Other interpretations: This section references other relevant interpretations of the issue. It includes interpretations by: – UN Special Rapporteurs – UN working groups – International and regional organizations – International and regional declarations |

|