How is tuberculosis (TB) a human rights issue?

What is TB?

What does TB stand for?

TB stands for tuberculosis, an airborne infectious disease caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis. TB typically attacks the lungs (pulmonary TB), although it can affect other parts of the body as well (extra-pulmonary TB). TB is usually transmitted through the cough, sneeze, or spit of a person with active TB. When a person breathes in these air droplets, TB bacteria enter the lungs. From the lungs, the bacteria can move through the blood to other parts of the body, such as the kidney, spine and brain.1

Many healthy people exposed to TB are able to successfully fight off infection. Their immune systems destroy the bacteria, eliminating any trace of exposure.2 However, other people may lack the resistance to prevent infection or disease.3 Infected individuals can progress to active TB disease and experience symptoms such as cough, chest pains, weakness, weight loss, fever and night sweats.4

If left untreated, TB kills more than half of those who develop active cases.5 People with HIV and other immuno-compromised states are at higher risk of developing TB infection and disease. Additionally, people with HIV and children are at higher risk for developing extra-pulmonary TB.6 Accurate diagnosis combined with treatment with anti-TB medicines can greatly reduce mortality rates.7 Yet while B is preventable and curable, barriers to accessing care and maintaining health hinder TB control efforts and contribute to a global rise in drug-resistant strains of TB.

What are latent TB and active TB?

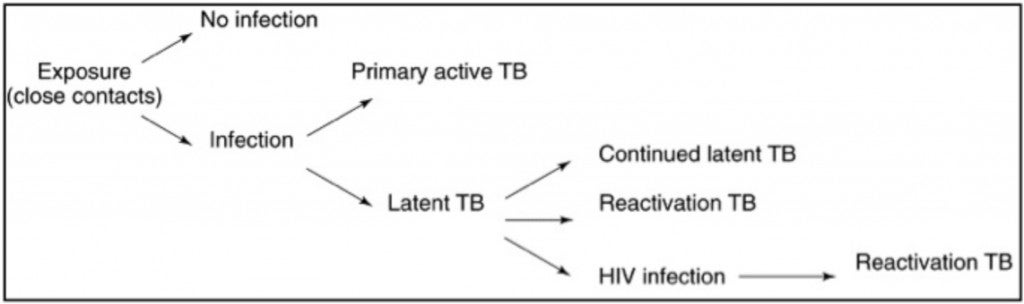

TB develops in two stages. The first stage, known as latent TB or TB infection, occurs when a person exposed to TB bacteria becomes infected.8 When the body’s immune system is unable to eliminate the bacteria, it may wall them off with tiny pieces of scar tissue known as granulomas. The bacteria stay in the body but remain dormant or inactive. The individual is infected, but does not have any symptoms and is unable to spread TB.9

The second stage, known as active TB or TB disease, occurs when the bacteria multiply in the body, usually causing the person to become sick.10 This can happen at any time, even many years after infection.11 People with active TB experience symptoms which can vary depending on whether they have pulmonary or extra-pulmonary TB.12 Additionally, people with TB of the lungs or throat can spread infection to others.13 The following diagram, adapted from Parrish et al., helps illustrate the interaction between latent and active TB:14

How is TB spread?

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the probability of developing TB infection and disease increase “with malnutrition, crowding, poor air circulation, and poor sanitation—all factors associated with poverty”.15 These risks are greater in crowded institutional settings such as prisons and detention centers. While TB bacteria are vulnerable to sunlight and fresh air, they can survive and circulate in closed, poorly ventilated environments. Individuals with active TB “can infect up to 10 to 15 other people through close contact over the course of a year”.16 Poverty and limited access to health care fuel the spread of TB by impeding diagnosis, treatment and care. Moreover, inappropriate treatment fuels drug resistance, resulting in higher rates of TB and greater disease severity, particularly in resource-constrained settings.

How is TB diagnosed?

There are several types of tests to determine if a person has been infected with TB. Sputum smear microscopy is one of the most widely used, particularly in high burden countries. It involves examining the sputum (lung fluid) of infected persons under a microscope to identify TB bacteria. While the test is fast and inexpensive, it tends to under-identify the number of infected persons (false negatives) and cannot test for drug resistance.

Drug susceptibility testing (DST) is another type of testing to determine if the bacteria are susceptible to treatment or resistant to drugs. For example, culturing involves growing TB bacteria in a laboratory to confirm infection and to test for drug susceptibility.17 It is currently the only method available to monitor patients’ response to treatment for drug-resistant TB. However, it can take weeks and is not always available.18 In 2011, 19 of the 36 countries with the high burden of TB did not have the recommended laboratory capacity to perform culture and DST.19

More sensitive diagnostic technologies have been developed in recent years. Gene Xpert MTB/RIF is a new rapid molecular test endorsed by the WHO. It can diagnose TB and drug-resistant TB within hours, and can be used at lower levels of the laboratory network than culture methods. Efforts to expand access and to decrease price are currently underway.20 Nevertheless, advances in TB diagnostic capacity must also be matched by advances in capacity to provide treatment.

What are MDR-TB and XDR-TB?

MDR-TB and XDR-TB refer to multidrug-resistant TB and extensively drug-resistant TB, respectively. Both can arise as the result of inadequate, incomplete or inconsistent treatment practices. People can also contract MDR or XDR-TB in settings where drug-resistant strains are prevalent. Treating TB requires strict adherence to a lengthy regimen of multiple drugs. Most cases of active, drug-susceptible TB can be cured with a standard six- to nine-month course of “four antimicrobial drugs that are provided with information, supervision and support to the patient by a health worker or trained volunteers.”21 This approach is known as DOTS, or directly-observed therapy, short-course.

MDR-TB does not respond to standard, first-line anti-TB drugs and is difficult and costly to treat. It accounts for about 3.7% of new TB cases each year and afflicts about 500,000 people. While 60% of these cases occur in Brazil, China, India, Russia and South Africa, MDR-TB has been documented in all countries surveyed to date.22 Yet in 2009, MDR-TB cases accounted for just 10% of all reported TB cases in high MDR-TB countries, and just a fraction of them were enrolled in treatment.23 XDR-TB is a form of MDR-TB “that responds to even fewer available medicines, including the most effective second-line anti-TB drugs.”24 XDR-TB has been identified in 84 countries, is virtually untreatable, and accounts for around 9% of all MDR-TB cases.25

Lack of diagnostic capacity has hindered effective responses to HIV-associated TB and drug-resistant TB. Few national TB programs can perform drug-susceptibility testing for first-line drugs, and even fewer have the capacity to test for second-line drug resistance. As a result, less than 5% of all MDR-TB cases are currently detected26 and an even smaller percentage of XDR-TB cases are detected.27 Many TB programs wait until the patient fails the standard drug treatment regimen before considering the possibility of drug resistance.28 It is estimated under 1% of persons with MDR-TB receive the quality of care that is considered standard in high-income settings. Effective management of MDR-TB and XDR-TB requires a commitment to equity: evidence-based diagnostics, therapies and adequate health care delivery, particularly in resource-constrained settings.29

What is the connection between TB and HIV?30

TB and HIV are overlapping epidemics which worsen health outcomes for those who are co-infected.31 An estimated 14 million individuals have TB-HIV, the majority of whom live in sub-Saharan Africa. At least one third of all people with HIV are co-infected with TB, and nearly one third of all TB deaths are among people co-infected with HIV.32 TB is the leading cause of death among people living with HIV worldwide—it accounts for 26% of HIV-related deaths, 99% of which occur in developing countries.33

TB and HIV health challenges

TB and HIV co-infection causes specific diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. TB and HIV exacerbate one another, accelerating the deterioration of immunological functions and resulting in premature death if untreated. Some evidence suggests that TB may exacerbate HIV infection and accelerate the progression from HIV to AIDS, although the mechanism remains unclear.34 At the same time, people living with HIV are 21 to 34 times more likely to develop active TB than those without HIV, making HIV the most powerful known risk factor for progression from latent to active TB. HIV co-infection also increases the risk of TB-related death.35

There has also been research into the interaction of HIV and drug-resistant TB. At the patient level, HIV infection has not been confirmed to be an independent risk factor for the development of MDR-TB. At the population level, however, HIV has increased the absolute burden of drug-resistant TB. Regardless of whether HIV infection is an independent risk factor for drug resistance, HIV has increased the pool of immuno-compromised patients who serve as hosts and vectors for all forms of TB, including MDR-TB.36

TB and HIV programming challenges

The HIV epidemic has overwhelmed and disrupted established TB-control programs, leading to high treatment failure rates and increasing the opportunity for drug-resistant TB to emerge and spread.37 Treatment for drug-resistant TB takes longer and is more complex, expensive, and toxic than treatment for drug-susceptible TB. It therefore results in lower treatment success rates and higher mortality rates, especially for those co-infected with HIV.38

Furthermore, while TB is confined to the lungs in most adult patients, it can be a systemic disease involving multiple organs in TB-HIV patients. All forms of extra-pulmonary TB, including disseminated TB, have been described in patients with HIV.39 Extra-pulmonary cannot be diagnosed through microscopy, which is the most available method of diagnosis worldwide. Therefore TB is also more difficult to diagnose in persons living with HIV.40 Diagnosis may also be delayed or incorrect due to logistical difficulties, such as the separation of sites for TB diagnosis and treatment from HIV diagnosis and treatment sites.

Collaborative TB-HIV activities

TB can be cured. While there is currently no cure for HIV, people can live healthy and productive lives with antiretroviral therapy (ART).41 Studies show that anti-TB drugs can prolong the lives of people with HIV by at least two years, even without ART, which can provide indefinite good health.42 Early TB screening and diagnosis, preventative therapy, treatment and adherence support to people living with HIV greatly increases the manageability of both diseases. Delivering integrated services, at the same time and location, is especially critical.43

The WHO recommends three types of collaborative TB-HIV activities: (1) establishing and strengthening mechanisms for integrated delivery of TB and HIV services; (2) reducing the burden of TB among people living with HIV and initiating early ART; and (3) reducing the burden of HIV among people with presumptive TB and diagnosed TB.44 In large part to the scale-up of such activities, TB deaths in people living with HIV declined by 25% between 2004 and 2011.45 Yet further progress is needed. In 2011, just 40% of TB patients were screened for HIV and just 7% of people living with HIV were screened for TB.46 The combination of HIV, TB and MDR-TB in prisons has created an urgent human rights crisis in many parts of the world—in African countries such as South Africa, Uganda, and Zambia;47 in Central and Eastern European countries such as Russia, Azerbaijan and Georgia; 48 and in Southeast Asian countries such as Cambodia, Indonesia and Thailand.49 For more information on HIV, AIDS, and human rights, please see Chapter 2.

How is TB a global epidemic?

TB is second only to HIV as the leading cause of death from an infectious disease worldwide.50 Approximately 2.3 billion people—one third of the world’s population—have been infected with TB, the majority of whom have latent TB and therefore do not have active symptoms and cannot transmit the disease to others.51 However, around one in ten infected persons goes on to develop active TB disease. There are currently an estimated 12 million active cases of TB worldwide and nearly 9 million new cases each year.

According to the WHO, Asia and Africa carry the greatest burden of TB, with India and China accounting for nearly 40% of all cases. Africa accounts for 24% of the world’s cases “and the highest rates of cases and deaths per capita”.52 In 2011, 1.4 million people died from TB and over 95% of these deaths occurred in low- and middle-income countries.53 While the TB death rate has dropped 40% between 1990 and 2011, the disease has never been eradicated in any country.54 Experts caution that progress remains uneven across economic and social lines. These inequalities, combined with growing resistance to anti-TB drugs, require urgent attention.

How is TB a Human Rights Issue?

Who Is Affected By TB?

Human rights are inextricably linked with who gets TB. According to the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB and Malaria (Global Fund):

Tuberculosis is a disease of poverty and inequality…. Many of the factors that increase vulnerability to contracting [TB] or reduce access to diagnostic, prevention and treatment services are associated with people’s ability to realize their human rights.55

A lack of respect for human rights fuels the spread of TB56 by creating conducive economic, social and environmental conditions. Key vulnerable groups include people living in poverty, ethnic minorities, women, children, people living with HIV, prisoners, homeless persons, migrants, refugees and internally displaced persons. They are more likely to be exposed to conditions that are conducive to TB development and less likely to have the information, power and resources necessary to ensure their health. Additional groups at risk include people who work in institutional settings, and people who use alcohol, tobacco and drugs.57

TB also undermines the realization of human rights by increasing vulnerability to the disease. People affected by TB suffer a double burden: the impact of the disease as well as the “consequential loss of other rights.”58 TB contributes to poverty, for example, by preventing people from working and by imposing high costs related to treatment and care. People can also be subjected to arbitrary and harmful measures such as involuntary treatment, detention, isolation and incarceration. Finally, TB-associated stigma and discrimination—and overlapping discrimination based on gender, poverty, or HIV status—can affect people’s employment, housing and access to social services.

These intersecting violations shape the contours of the global TB epidemic. According to the WHO, the number of people falling ill with TB each year is declining and the death rate has dropped by 40% between 1990 and 2010.59 Yet this progress is offset by glaring inequalities: over 95% of all TB cases and deaths occur in developing countries and 79% of all TB-HIV cases are concentrated in Africa.60 To mount an effective response to TB, public health approaches must be informed by and harmonized with the protection of civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights. Human rights are relevant to achieving universal access to quality TB prevention, diagnosis, treatment, care and support in at least three ways:

Human rights violations exist “as core features of risk environments, as barriers to care, and as social determinants of poor health and development”.61

Human rights provide a framework for holding governments and third parties responsible for developing and implementing evidence-based and rights-based responses to TB.

Human rights provide a framework for empowering people to reduce their vulnerability to TB and to participate in directing the policies, programs and practices that affect them.

This section examines key human rights issues that impinge on the ability of individuals and communities to maintain health, to access relevant information and services, and to avoid discriminatory and harmful measures. It also identifies interventions that can assist stakeholders in developing inclusive, equitable and effective human rights-based approaches to TB.

How Do People Get TB?

TB is most often seen among individuals and communities who share specific biosocial risk factors for the disease, including poverty, malnutrition, crowding and HIV.62 These in turn are embedded in larger economic, social and political realities known as the structural determinants of health.63 TB has no natural constituencies. Instead, it clusters wherever weak and inequitable social policies create vulnerability to the disease. TB risk increases with a lack of access to education, poor nutrition, inadequate housing and sanitation, poor health services and facilities, lack of employment and social security, and political exclusion.64 According to Hargreaves et al.:

Key structural determinants of TB epidemiology include global socioeconomic inequalities, high levels of population mobility, and rapid urbanization and population growth. These conditions give rise to unequal distributions of key social determinants of TB, including food insecurity and malnutrition, poor housing and environmental conditions, and financial, geographic, and cultural barriers to health care access. In turn, the population distribution of TB reflects the distribution of these social determinants, which influence the 4 stages of TB pathogenesis: exposure to infection, progression to disease, late or inappropriate diagnosis and treatment, and poor treatment adherence and success.65

For example, people in urban slum housing and people in prison may share vulnerabilities in terms of poor physical space, standard of living and access to health care. Similarly, women and migrant workers may share vulnerabilities in terms of decreased economic, social and legal agency. People who use drugs and people living with HIV may share vulnerabilities in terms of stigmatized and often criminalized medical status. And finally, refugees and homeless populations may share vulnerabilities in terms of mobility and exclusion from social services. These factors in turn determine access to timely and appropriate diagnosis, treatment and care, as well as impact TB-related outcomes. According to Lonnroth et al.:

The risk of adverse health, social and financial consequences is determined by socioeconomic status, gender, social values and traditional beliefs in the community, the availability of social support services within the health care and social welfare systems, labour laws, and sick leave and pension systems.66

The following social and structural determinants play a significant role in fuelling different stages of TB and shaping the global epidemic.

Poor Physical Environment

Poor living and working conditions increase the risk of TB exposure and infection. Specific risk factors include more frequent contact with persons with active TB, as well as crowding and poor ventilation in homes, workplaces, health care settings, public transportation and prisons. Indeed prisons offer one of the most compelling examples of how substandard physical environments increase vulnerability to TB. Todrys and Amon describe the situation in many under-resourced prison cells in Africa:

Overcrowding—resulting in and exacerbating food shortages, poor sanitation, and inadequate health care—contributes to the spread and development of disease. Minimal ventilation, poor isolation practices, and a significant immuno-compromised population also facilitate the transmission of TB and the development of TB disease.67

This dangerous environment helps explain why TB is the leading cause of death among the world’s prisoners, who account for 8.5% of all TB cases.68 While an estimated 9 million people are incarcerated on a given day, four to six times this number pass through the prison system each year due to high prisoner turnover. Prisons act as a conduit of TB transmission, spreading the disease among prisoners, prison staff, visitors and the greater community.69 As a result, prisons can have TB levels up to 100 times higher than the non-prison population, and can account for up to a third of a country’s total TB burden.70 The high concentration of active cases in these settings also accelerates the development of drug resistance. In some prisons up to 24% of TB cases are MDR-TB.71

Similar mechanisms are at work in other crowded, poorly ventilated and underserved settings, such as in urban slum housing, barracks that house men who work in mines, and refugee and internally displaced persons (IDP) camps. For example, the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) reports that 85% of the world’s 32 million refugees and displaced persons originate from, and remain in, countries with high burdens of TB. The poor living conditions in many refugee and IDP camps can facilitate TB development, making the disease an increasingly important cause of sickness and death among these populations.72

Poor Health Status

Poor health increases the risk of TB infection, progression to active disease and poor clinical outcomes. Coexistent conditions such as HIV, malnutrition, alcoholism, smoking-related conditions, silicosis, diabetes and cancer further weaken the immune system.73 The impact of poor health status can be seen at the population level. In a recent analysis of 22 countries with 80% of the world’s TB burden, experts estimated that total new cases might be reduced by eliminating the following health risks: malnutrition (34% fewer cases); indoor air pollution (26.2%); active smoking (22.7%); HIV infection (17.6%); alcohol use (13.1%) and diabetes (6.6%).74

The dynamic between TB and poor health is particularly lethal in institutional settings such as hospital wards and prison cells. For example, prisons often hold a high proportion of susceptible or immuno-compromised people, including drug-dependent individuals targeted by punitive drug laws.75 This environment contributes to high risk of TB, HIV, hepatitis C and hepatitis B, endangering prisoners and the larger community. Risk factors include overcrowding, malnutrition, poor access to health care, sexual activity (including sexual violence), inability to access safe injecting equipment, and lack of access to drug treatment and opioid substitution therapy.

Even as overall TB prevalence is declining, it is rising in many parts of sub-Saharan Africa and the former Soviet Union due to the epidemic of HIV, TB and MDR-TB in prisons.76 For example, Russia has the second largest prison population in the world after the United States, with 850,000 to one million prisoners.77 Many are incarcerated for drug-related offenses. Overcrowding, poor nutrition and medical care, and inadequate infection control practices fuel TB in the country’s many prisons and prison colonies. The Andrey Rylkov Foundation explains:

Medical resources are limited and demands on the services are high. Although antiretroviral drugs are available, there is no HIV prevention and no formal drug treatment. When HIV treatment is available, the supply is inconsistent as is the treatment of TB and there are no second line drugs available to treat [MDR-TB]…. Collaboration and integration with community health services is poor, and community hospitals are often unable to save the lives of patients who are released from prisons in poor health, only to die outside.78

People who work in prisons, hospitals and others health care settings can also face increased risk of TB. According to the WHO, health care workers have an ethical obligation to attend to TB patients, even if it involves some degree of risk. At the same time, they are entitled to adequate protection against contracting TB. Therefore, governments and health care systems have a duty to provide the necessary goods and services to ensure a safe working environment.79 The WHO’s 2010 Guidance on ethics of tuberculosis prevention, care and control (TB and Ethics Guidance) provides further information about health care workers’ rights and obligations with respect to TB.80

Beyond health care, TB is linked with other occupational exposures such as mining. Prolonged exposure to silica dust in mine shafts increases risk of lung diseases, particularly TB. According to the AIDS and Rights Alliance for Southern Africa, “[h]igh rates of HIV transmission and confined, humid, poorly ventilated working and living conditions further increase the risk of TB among mine workers.”81 As miners cross borders in search of work, they spread and often bring it back to their home countries. A recent study of men with TB in Lesotho found that a quarter had worked in South African mines.82

TB and HIV infection increase vulnerability to human rights violations. People with TB often face abuse, stigma, and discrimination—manifested in “social ostracism, loss of income or livelihoods, denial of medical services or poor care within the health sector, loss of marriage and childbearing options, violence and loss of hope/depression (internalized stigma).”83 Experts note that in areas of high HIV prevalence, “TB is perceived as a marker for HIV positivity; therefore, HIV-associated stigma is transferred to TB-infected individuals.”84 This phenomenon is confirmed by one Kenyan man, who noted: “I have been stigmatized by friends who thought I was HIV positive. Every time they saw me take the drugs they thought I was taking [antiretroviral medicines].”85

TB thus contributes to ongoing cycles of poverty, vulnerability and poor health. Most costs related to TB arise prior to treatment: medical tests, drugs, consultation fees, transportation, and lost income. Additionally, TB diagnosis and treatment themselves can also be very expensive. Accessing care can cause people to incur debt or sell household assets,86 leading to “catastrophic expenditures” which can impoverish entire families.87 People with TB may lose income because they are sick or seeking care. They may lose their jobs entirely or be unable to find work due to the stigma associated with the disease. Finally, children whose caregiver loses income due to TB may be deprived of education, adequate nutrition and access to social services. For more information, see the section below on “Vulnerability among children”.88

Poor Access to Health Services and Systems

Poor access to health services creates gaps in TB diagnosis and treatment, contributing to higher levels of active TB cases, worse clinical outcomes and the development of drug resistance.89 At an individual level, economic, social and legal factors often delay and impede contact with health care systems. Common barriers include a lack of money, difficulty arranging transportation to health facilities, lack of information about treatment options, fear of being stigmatized for seeking a diagnosis, and lack of social support in the event of sickness.90 For many, maintaining employment may take precedence over maintaining health. The WHO states:

Treatment for TB, particularly M/XDR-TB, is lengthy, complicated and expensive. Providing uninterrupted treatment and care remains a challenge for the health systems in many countries. People without access to a social safety net must often choose between following treatment to get well or working to support their families. Not completing treatment often means that people will fall ill again.91

At a systemic level, vulnerable and at risk groups are also less likely to have access to functioning health care systems with appropriate treatment options, adequate patient referral chains, and strong mechanisms for coordinating care.92 This is often the case in urban slums and in prisons, particularly in parts of Africa, Asia and the former Soviet republics. For example, one study on Georgian prisons noted a lack of coordinated TB screening, delays in diagnosis and therapy, unmanageable case loads, substandard facilities, and poor follow-up of patients.93 Another Russian study on drug dependent TB-HIV patients documented treatment gaps following release from prison or transfers among TB facilities.94

Mobile and migrant populations are especially likely to experience fragmented or interrupted care, including total exclusion from social services. Affected groups include migrant workers, undocumented persons, the urban homeless, refugees and the internally displaced. According to Human Rights Watch:

Normally, TB is easily and cheaply treated. However the prevalence of difficult to treat drug-resistant strains of TB, high incidence of co-infection with HIV, lack of cross-border mechanisms for referral and follow up care and surveillance, and the difficulty of treatment adherence while in transit, make mobile and migrant populations a serious health challenge.95

Even where there is point-of-care diagnostics or treatment (i.e., provided where people live or work), problems may persist “when HIV and TB are not treated together aggressively or, cross-border referral and follow up is too slow or insufficient, drug sensitivity is not properly detected.”96 Legal insecurity, language difficulties and cultural barriers can compound these access issues, especially for people who migrate in search of work. According to Naing et al.:

Transnational migrant workers are commonly surrounded by difficult and exploitative circumstances, which may be a result of their terms of employment and often precarious legal status…. Migration itself also has a major impact on access to and utilization of health services by migrant and host populations. There are many barriers to access health services for migrants, such as the fact that migrants need documents to be able to get healthcare services without fear.97

In South Africa, for example, Human Rights Watch has documented cases in which migrants were denied emergency TB treatment because they lacked identity documents or were foreign. As a result, many were forced to visit multiple facilities or to go without treatment, resulting in “late diagnosis and treatment and poorer overall health in migrant communities”.98

Unequal TB Treatment and Care

Effective TB diagnostics and therapies have been available for decades, yet many individuals continue to receive substandard care or none at all. This may be due to poverty or other marginalized status. For example, States have a duty to ensure that prisoners receive adequate health services, and that they are at least the same standard of care as those provided to the general population. The limited provision of TB services in prisons described above violates international human rights law.

Additionally, many people who use drugs face unduly restrictive conditions in accessing TB services. This is particularly problematic in Russia, where inpatient treatment is the norm and harm reduction services are denied. If patients leave TB clinics to obtain drugs, they are punished with discontinuation of TB treatment.99 According to the Andrey Rylkov Foundation, the “[i]nability of the health system to offer adequate drug treatment creates an institutionalized ‘trap,’ when drug dependent patients are excluded from stable TB treatment de-facto.”100

Treatment disparities are also linked to global funding and policy inadequacies in resource-constrained settings.101 Existing treatment standards sometimes fail to account for the flexibility required to effectively manage drug resistant TB. Global TB policy has emphasized inexpensive, standardized interventions to treat MDR-TB in low-income settings, despite the success of flexible, tailored protocols in high-income settings. As a result, less than 1% of people with newly diagnosed MDR-TB receive treatment that is considered the standard of care in the United States. Additionally, these divergent approaches to MDR-TB treatment have increased the intensity and scope of the epidemic.102

The Green Light Committee Initiative (GLC) was established to address unequal access to MDR-TB treatment and care, including access to affordable second-line drugs and scale-up of MDR-TB services.103 The Global Drug Facility, established in 2001, provides TB drugs to countries that could otherwise not afford them either in the form of grants or at the lowest possible price. At the end of 2011, 20 million treatment courses were delivered to 93 countries.104

Yet due to a lack of market incentive, TB continues to receive little attention from companies that develop improved medicines. To address this neglect, The Human Rights Guidelines for Pharmaceutical Companies in relation to Access to Medicines were created to provide guidelines for pharmaceutical companies on issues including transparency, quality, clinical trials, neglected disease, patents, pricings, ethics, marketing and partnerships.105 Guidelines 23-25 address the steps that pharmaceutical companies should take to address the neglect of poverty-related diseases. The right to the highest attainable standard of health requires that existing medicines are accessible as well as that much-needed new medicines are developed as soon as possible.106

Vulnerability Among Women

TB afflicts women during their most economically active years and is among the top three causes of death among women aged 15 to 44 worldwide. In 2011, an estimated one third of the 8.7 million new TB cases were among women and 500,000 women died from TB.107 TB is linked with poor reproductive health outcomes, such as risk of infertility, premature birth, obstetric morbidity, and low birth weight. 108 According to the WHO, vulnerability to TB is related to women’s unequal social status and economic dependence:

Women in many countries have to overcome several barriers before they can access health care. Where they undertake multiple roles in reproduction, production and child care, they may be left with less time to reach diagnostic and curative services than men…. Women may be given less priority for health needs and generally have less decision-making power over the use of household resources. They often have less knowledge of TB, especially of its signs and symptoms, than men, related to the higher rate of illiteracy among women than among men worldwide.109

Women often wait longer to seek diagnosis and treatment for TB. This in turn can “increase the severity of their illness, decrease the success of treatment, and raise the risks that they will infect others.”110 Where TB treatment is provided mostly via in-patients modes—the norm in many former Soviet countries—women may face particular difficulty adhering to treatment due to their child care responsibilities or inability to leave home for extended periods. While men and women may both face economic consequences related TB stigma, women can also face lost marriage prospects, divorce, desertion and separation from their children.111

Gender-based inequality can also impair women’s ability to exercise and claim their human rights, including the rights to information, participation, freedom of movement, privacy and individual autonomy, and health.112 According to the WHO:

Gender discrimination, even when not directly related to health care—for example denying girls and women access to education, information, and various forms of economic, social and political participation—can create increased health risk. Even if the best public health services are available, a woman has to be able to decide when and how she is going to access them, and that implies that she has to have the ability to control and make decisions about her life.113

Vulnerability Among Children

Children are vulnerable to TB for interrelated biological and social reasons. Each year there are approximately 500,000 new TB cases and up to 70,000 TB deaths among children. TB in children often goes undetected because their symptoms are overlooked, unrecognized as TB, or difficult to diagnose and confirm.114 Key risk factors for TB in children include contact with infected persons, HIV infection, age less than five years, and severe malnutrition.115 According to the WHO:

Children are exposed to TB primarily through contract with infectious adults—with special risk in high TB-HIV settings—and will continue to be at risk for TB as long as those adults remain untreated. Curing TB and preventing its spread in the wider community is thus one important strategy to reducing children’s vulnerability to TB.116

TB in children often rapidly and imperceptibly progresses from infection to disease.117 Infants and young children are at particular risk of TB meningitis, a severe and often fatal form of TB, and HIV-infected children have an especially high risk of developing TB meningitis. While the BCG (Bacille-Calmette-Gurin) vaccine can protect infants and children against certain severe forms of TB in children, it is no longer believed to be effective in protecting against pulmonary TB.118 This is particularly problematic for adolescents who are at risk of developing active pulmonary TB.119

According to the WHO, “[c]hildren with TB are often poor and live in vulnerable communities where there may be a lack of access to health care.” Moreover, children who are sick with TB may be taken out of school, depriving them of their right to education. The WHO notes:

Already marginal households that lose income or incur debt due to TB will experience even greater poverty as budgets are cut and assets sold. If their primary care giver is ill or is preoccupied with caring for other ill family members, the child’s care and education may be neglected. If the principal family provider is ill and cannot work, children risk malnutrition, which increases susceptibility to TB and brings with it lifelong deleterious effects on both health and education.120

These risk factors are heightened for orphaned children, street children and other vulnerable categories of youth, who are more likely to experience housing insecurity, poor nutrition, lack of access to care, and lack of access to education and information.121 It is estimated that there are over 10 million children orphaned as the result of a parent dying from TB.122

What Happens to People Affected by TB?

Current responses to TB often fail to respect the human rights of people who are vulnerable, at risk or affected by the disease. Under international human rights law, States must respect, protect, and fulfill the human rights of all people, including those with TB. The duty to respect means that States must refrain from interfering with the enjoyment of rights. The duty to protect means that States must prevent other actors from infringing on these rights. Finally, the duty to fulfill means that States must adopt all appropriate legislative, administrative, budgetary, judicial, and other measures toward the full realization of these rights.123

To fulfill the right to health, States must take immediate and targeted steps to ensure that health services, goods and facilities are available, accessible, acceptable and of quality. As the Global Fund notes, “[t]he right to non-discrimination, including on the grounds of social and health status, is an immediately enforceable obligation”.124 Additionally, every TB patient is entitled to benefit from advanced and high-quality treatments, medicines, and diagnosis methods on an equitable and affordable basis, consistent with the right to benefit from scientific progress and its applications.125 States therefore have a core obligation to ensure access to high quality TB treatment, care and support, and to reduce vulnerability by guaranteeing the underlying determinants of health.

Nevertheless, widespread concern over TB, MDR-TB, and XDR-TB has many led governments to “routinely cite TB as an example of when it may be justified to limit patients’ rights to protect the health and safety of the public.”126 International law provides qualified support. Derogation clauses in the two key international human rights treaties—the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR)127 and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR)128—permit restrictions on individual rights in limited circumstances, provided that they are in accordance with the law, strictly necessary to achieve a legitimate objective, and consistent with other human rights provided for.

Accordingly, many governments have enacted rights-limiting measures in the name of TB control, such as detention of infected persons in prisons, forcible admissions into hospitals, home arrests, and travel restrictions. Yet the extent to which public health concerns may constrain individual human rights is closely circumscribed by the Siracusa Principles, a non-binding document adopted by the UN Economic and Social Council in 1984.129 These principles state that restrictions on human rights must be:

- provided for and carried out in accordance with the law;

- directed toward a legitimate objective of general interest;

- strictly necessary in a democratic society to achieve the objective;

- the least intrusive and restrictive available to reach the objective;

- based on scientific evidence and neither arbitrary nor discriminatory in application; and

- of limited duration, respectful of human dignity, and subject to review.130

In practice, the Siracusa Principles do not provide governments with adequate guidance for developing measures that protect public health while respecting human rights.131 Public health authorities are able to exploit ambiguous provisions in the law to oversee and compel treatment, frequently in correctional facilities. This can result in rights restrictions beyond those explicitly called for.132 According to Amon et al.:

[It is argued] that involuntary detention may legitimately be used in a limited number of cases when patients infected with drug-resistant strains of TB refuse treatment…. In practice, however, some countries have invoked sweeping rights-limiting policies that affect TB patients who have not been offered the global standard of care…. Reliance on compulsory detention, when less intrusive and less restrictive measures have proven feasible and effective, is not consistent with human rights principles.133

The authoritative interpretations of the Human Rights Committee, which oversees state implementation of the ICCPR, provides further guidance on when human rights can be restricted in the name of public health. According to Todrys et al., the 1999 General Comment on freedom of movement “stresses the need for restrictions to be provided for by law, demonstrably necessary, consistent with other rights in the ICCPR, and non-discriminatory. In particular, the Committee dwells on the requirement of necessity for a proposed restriction”.134

Incarceration and other coercive TB measures unjustifiably interfere with patients’ human rights and dignity.135 They also neglect more effective, rights-respecting alternatives—such as the provision of community-based DOTS, adherence support (e.g., counseling or nutritional supplements to reduce the side effects of medicine), and in-patient or out-patient treatment options.136 These ambulatory and community-based models of care137 have been shown to be highly successful, especially in resource-constrained settings.138 Moreover, there is strong evidence that rights-limiting measures increase vulnerability to TB by subjecting individuals to conditions that favor TB infection, transmission, illness and death.139 They are generally considered by human rights experts to be “unnecessary from a scientific standpoint and dangerous from a programmatic perspective”.140

As an important caveat, the implementation and enforcement of rights-restricting measures related to TB varies widely at the local level. However, as Todrys et al. note, “government authorities and local laws sometimes do not fully meet, or entirely disregard, the requirements in the Siracusa Principles that restrictions on right in the name of public health be strictly necessary and the least intrusive available to reach their objective”.141 The following sections describe different laws, policies and practices which undermine the health and other human rights of people affected by TB.

Criminalization of TB Status

Criminalization of TB patients who do not complete treatment is not an effective strategy for TB control and treatment and violates basic human rights.142 Failure to complete treatment can lead to imprisonment in certain countries. Criminalization however discourages individuals with TB symptoms from seeking diagnosis and treatment for fear of imprisonment and can thereby delay diagnosis and increase the risk of transmission:143

People are more likely to use HIV and TB services if they are confident that they will not face discrimination, their confidentiality will be respected, they will have access to appropriate information and counseling, and they will not be coerced into accepting services.144

Criminalization and imprisonment of TB patients increases discrimination and stigmatization and intensifies the wrong done to people who are already ill. Many individuals with TB do not complete treatment due to a lack of understanding of or education about treatment methods, lack of access to drugs, and negative side effects from treatment.145

TB legislation is often focused on punishing patients who “default” from treatment rather than access to quality and affordable medicines. In some countries, patients can be imprisoned for months without proper information, legal representation, or an opportunity to defend their actions. For example, in Kenya, a patient that was placed in jail stopped taking his medicine because he had severe negative side effects that were exacerbated by hunger caused by drought. Another patient was never told how long to stay on treatment, stopped taking his medication once he felt better, and was placed in jail as a result. Kenya’s criminalization and imprisonment mechanisms are contrary to the internationally recommended standards.146 TB patients are placed in prisons with criminal offenders, often in cramped living environments and without proper nutrition. While in jail, they can easily infect other prisoners or be re-infected. There are little to no mechanisms in place to ensure that other prisoners do not contract TB from the infected individuals, re-infect individuals once they are well, or spread the disease back to their homes and communities when they are released.147

Involuntary Treatment

The issue of involuntary treatment centers on the question: when, if ever, is it justified to compel treatment of TB patients over their objection? As a preliminary matter, the Siracusa Principles state that with respect to rights-restricting measures invoked on the grounds of public health, “[d]ue regard shall be had to the international health regulations of the World Health Organization.”148 The WHO affirms that it is unethical to force TB patients to undergo treatment if they have objected to it; moreover, it is also unlikely to achieve its intended public health purpose. The WHO’s TB and Ethics Guidance states in relevant part:

In general, TB treatment should be provided on a voluntary basis, with the patient’s informed consent and cooperation… [E]ngaging the patient in decisions about treatment shows respect, promotes autonomy, and improves the likelihood of adherence. Indeed, non-adherence is often the direct result of failure to engage the patient fully in the treatment process.149

Contagious TB patients who refuse treatment and/or infection control measures can be isolated to prevent the spread of disease. Within isolation, if patients provide an informed refusal of treatment, their decision should be respected. The WHO states:

Forcing these patients to undergo treatment over their objection would require a repeated invasion of bodily integrity, and could put health-care providers at risk. Moreover, as a practical matter, it would be impossible to provide effective treatment without the patient’s cooperation.150Involuntary Isolation151

The WHO’s TB and Ethics Guidance states that compelled isolation (and detention) is to be viewed as a last resort measure, and limited to three “exceptional circumstances” when an individual is:

The given justification is that TB patients who do not voluntarily undergo diagnosis, or who fail to adhere to treatment or infection control measures, pose serious risks to public health. The WHO further states that in rare cases where compulsory isolation is justified, measures must comply with the procedural limitations set forth in the Siracusa Principles.153

Nevertheless, compulsory isolation often violates these guidelines. First, it cannot be considered an effective “last resort”, as it comes at the expense of less-restrictive measures. Community-based treatment models have proven effective to ensure patients complete treatment, while also preventing the spread of TB, when compared to more traditional hospital-based care.154 This has been demonstrated in South Africa,155 which has the second highest incidence of TB cases in the world, the highest rate of MDR-TB in Africa, and the fourth highest prevalence of HIV/AIDS.156 Additionally, more attention is needed to support access and adherence to treatment in the first place. For example, the severe side effects of MDR-TB drugs can pose problems: “Many adults default with their treatment, after which the TB germ develops resistance to the routine antibiotics with which we treat the condition. They then infect their children with MDR (TB).”157

Second, compulsory isolation measures are often ineffective in containing TB. South Africa requires the isolation of MDR-TB and XDR-TB patients in specialist provincial hospitals for a minimum of six months. In some cases patients are held as long as two years; in others they are released after just six months. Many TB patients are isolated in sub-standard conditions that violate their basic constitutional rights as well as South African health legislation.158 According to Amon et al., because no assessment of infectiousness is ever made, these patients lack access to the drugs they need, “resulting in almost universal mortality.”159 In addition, given the size of the epidemic, hospital space and cost constraints make a blanket policy of isolation impractical.160

The Open Society Foundations notes that Kenya is also investing limited anti-TB resources in building expensive isolation facilities. Despite the WHO’s guidance that “reasonable social supports” be provided to isolated patients and their families, in practice this may not take place. In Kenya, South Africa and elsewhere, TB patients who are isolated may be required to leave their jobs and their families, depriving their dependents of support and increasing their vulnerability to TB. In many cases, compulsory isolation simply “fails to protect the rights of individuals, fuels stigma and discrimination, potentially worsens health status, and is deemed unnecessary from a public health standpoint.”161

Involuntary Detention

According to the WHO TB and Ethics Guidance, the three “exceptional circumstances” described above—which determine whether involuntary isolation is ever justified—apply equally to involuntary detention. Similarly, the five Siracusa criteria set forth the applicable safeguards for implementing involuntary detention. The justification often given is that involuntary detention is justified to protect “both the human right to health and health as a public goods,” particularly in the face of high TB, MDR-TB and XDR-TB rates.162

Involuntary detention, however, has not been proven to be an effective TB treatment and prevention mechanism. It can deter sick individuals from seeking diagnosis. Additionally, it does not prevent the spread of disease: because of the delay between diagnosis and admission to a facility, widespread infection may have already occurred. Poor hygiene and living standards at confinement facilities themselves can further spread infection to healthcare workers and visitors, which in turn can spread the infection to families and communities.163 Lastly, drug-resistant TB has shown to be no more infectious than drug-susceptible TB, so more extreme measures are not justified for drug-resistant, including XDR-TB, patients.

The 2007 WHO Guidance on human rights and involuntary detention for xdr-tb control states that governments should make prevention and access to accurate diagnosis and high-quality treatment high priorities. Involuntary treatment or compulsory detention may be used to prevent or treat XDR-TB cases only as a last resort, only when all voluntary measures have failed or have been insufficient, and only when all criteria of the Siracusa Principles have been met.164 However, involuntary detention often does not comply with applicable human rights principles in practice. According to Sacco et al.:

… [P]ersons with TB are detained even when they are capable of adhering to infection control regimens and to treatment…. Treatment in the community has been shown to be a more effective and less rights-violating alternative to detention of people with TB, who in any case have an absolute right to freedom from ill-treatment in confinement and to due process to challenge their confinement.165

Additionally, while involuntary confinement in theory should only limit one right—a patient’s freedom of movement—it has the potential to and often does limit many other rights, including a patient’s right to dignity if the health facility conditions are substandard, right to work if they lose their job while involuntary confined, right to raise a family if they are forcibly separated from young children and have no alternative caregiver, and right to housing if they lose their homes as a result of confinement.

South Africa demonstrates an evolving approach to detention as a means of addressing TB. Until recently, TB patients who entered the public health system faced the risk of incarceration, whereas those who could afford private sector healthcare could be treated at home. As an outgrowth of HIV advocacy, and due in part to the high co-infection of HIV and TB in South Africa, South Africa’s National Strategic Plan (NSP) now includes TB in its goals and strategic objectives.166 It recognizes human rights violations against TB patients and outlines strong commitments to protect their rights and to move towards community-based care.167 Specifically, it calls for the development and implementation of “a national policy that permits the detention of patients with drug-resistant TB only when necessary and under conditions consistent with international good practice.”168

Given evidence of the effectiveness and scalability of community-based delivery models in resource-constrained settings, involuntary detention could rarely be considered the least restrictive means available—particularly if less restrictive means have not been applied. Moreover, involuntary detention is often applied in an arbitrary and discriminatory manner based on the ability to pay for health care. According to Amon et al., “[t]he ability to pay for health care is not a rational basis for deciding who should be deprived of liberty and who should not.”169

Failure to Address Stigmatization and Discrimination

People with TB often face profound stigma and discrimination.170 They can face social rejection by family, friends and community members, expulsion from school, reduced income and loss of employment.171 A recent analysis of TB stigma literature notes:

TB stigma has a more significant impact on women and poor or less-educated community members, which is especially concerning given that these groups are often at higher risk for health disparities. TB stigma may, therefore, worsen preexisting gender- and class-based health disparities.172

The WHO notes that patients may go to great lengths to escape stigma and isolation, “lengths that may prolong both their own suffering and the length of time they remain infectious.”173 Infected individuals may hide their TB status from their families; at the same time, families may conceal TB-related death causes from the larger community.174 TB stigma has been identified as a barrier to timely TB screening, diagnosis, care-seeking and adherence to and completion of treatment:

Individuals with TB-like symptoms may first attempt to see private physicians so as to avoid TB stigma. Because private clinics typically have longer waits for appointments, this may translate to diagnostic delay and increased financial costs for patients.175

Once treatment has begun, TB patients may fear being identified and drop out of treatment programs. TB related stigma and discrimination make people more afraid to learn their status, disclose their status to others, to seek care and to adhere to treatment. This increases their vulnerability, suffering and loss of other human rights. People with TB are also more likely to suffer from discriminatory measures that perpetuate stigma and exclusion. For example, in one district in Ghana, people with TB are prohibited from selling goods in public markets or attending community events. While the right to nondiscrimination is an immediately enforceable obligation under international human rights law, in practice there are few domestic laws prohibiting discrimination on the basis of TB or suspected TB status.

Societal, institutional and legal stigmatization of TB violates the human rights of individuals with TB while also impeding larger efforts at prevention and control.176 The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights notes that “[n]on-discrimination and equality are fundamental components of international human rights law” and essential to the exercise of the right to health.177 State parties to the ICESCR are therefore obligated to take all appropriate measures to eliminate discrimination against people on the basis of TB status. Direct measures include reform of laws and policies that discriminate against people on the basis of TB status. An example might include legislation requiring people showing active TB symptoms to enter hospitals, where they risk exposing others and being exposed to drug resistant forms of the disease.178 Indirect measures focus on the conditions and attitudes contributing to discrimination, including by private individuals and entities. Education and information play an important role: this approach has been well-documented to reduce the stigma attached to HIV and to mobilize government and community resources in efforts to combat the disease.179

What are current interventions and practices

in the area of TB?

The interventions, practices, programs and policies outlined below all strive to end the HIV epidemic and support people living with TB to live lives with dignity. Some of the interventions and practices focus on the biomedical response to TB including recommended treatments, whereas others and policies focus on vulnerable groups and human rights issue areas.

Universal Access to Treatment as Prevention

Quality Assured Diagnostics

A sputum smear microscopy test is the most widely used method to detect TB. However, this test has low sensitivity, especially in HIV-positive individuals and children, and is unable to determine drug-resistance. TB can also be diagnosed with culture methods or rapid molecular tests in countries with more developed laboratory capacity.180 A new rapid, fully automated test called the Xpert MTB/RIF test provides a highly accurate diagnosis that identifies the presence of TB and drug-resistant TB. The new test is not as susceptible to human error and allows people to be offered proper treatment immediately.181

Drug Susceptibility Testing

Drug resistant TB diagnosis depends on the slow process of bacterial culture and drug susceptibility testing. Drug resistant TB patients may be inappropriately treated during this slow diagnostic process, and drug-resistant strains and resistance may continue to spread during this time.182 Lack of diagnostic capacity is a critical barrier to effective TB treatment.183

People with latent TB should benefit from interventions to prevent progression to active disease, including isoniazid preventive therapy.184 This is true even for patients who live in resource-constrained settings.

Adherence Support

Adherence support refers to medical, social and economic initiatives to help patients follow and benefit from TB treatment and care. According to Partners In Health, it “specifically targets TB patients who face barriers to accessing care: the elderly, pregnant women, geographically isolated patients, and patients who suffer from socio-economic problems such as poverty and alcoholism”.185 Examples include providing travel vouchers or transportation to health care facilities, food packages, peer support, education and follow-up, and engaging community health workers to accompany patients as they access health care.186 These initiatives help ensure continuity of care and increase patients’ chances for complete recovery.

HIV Screening and Treatment

As part of its policy guidelines on collaborative TB-HIV activities, the WHO recommends offering routine HIV testing to patients with presumptive or diagnosed TB, as well as to their partners and family members.187 As the Global Fund notes:

Examples of a collaborative approach include HIV counseling and testing, the use of antiretroviral therapy in TB-HIV patients and isoniazid preventative therapy to reduce TB risk among HIV patients. These measures require strong links with the HIV community.

Harm Reduction Measures

Ensuring access to harm reduction measures is an effective approach to reducing vulnerability to TB, particularly among people who use drugs and prisoners. “Harm reduction” refers to policies, programs, and practices aimed at reducing drug-related risks and harms, rather than on reducing and punishing drug use.189 Examples include needle and syringe programs, safe injection facilities, opioid substitution therapy, overdose prevention, outreach and education and decriminalization of people who use drugs. Harm reduction strategies form a part of States’ human rights obligations.190 They are recommended by the WHO in its Policy Guidelines for Collaborative TB and HIV Services for Injecting and Other Drug Users.191 Specific recommendations include treatment adherence programs, continuity and communication across all health care access points, and provision of the same services to drug users as provided to the general civilian population.192 For more information on harm reduction and human rights, please see Chapter 4.

Palliative Care

Providing home-based palliative care for TB and related comorbidities is a necessary complement to effective, rights-respecting TB treatment and care.193 Palliative care is “seeks to improve the quality of life of patients diagnosed with life-threatening illnesses through prevention and relief of suffering” and addresses the psychosocial, legal and spiritual aspects associated with life-threatening illnesses. Palliative care measures in the context of TB include pain control, relief of TB symptoms and drug side effects, nutritional support, ongoing psychosocial support and end-of-life care. Palliative care services can promote the health and improve the lives of people with TB by implementing effective infection-control in the home and in-patient settings, intensifying case finding and referral to treatment, providing effective treatment support, among other benefits.194 For more information on palliative care and human rights, please see Chapter 5.

Models of Delivery

Point of Care Diagnostics and Treatment

There is an overemphasis on clinical interventions for Vulnerable and at risk groups, including harmful detention and in-patient hospitalization of patients with drug resistant TB. This is despite limited evidence of the effectiveness of this approach, and ample evidence of the effectiveness of ambulatory and community-based models of service delivery. More attention is needed to providing individuals with quality treatment and care where they live and where they work. Point-of-care diagnostics and treatment are needed to reach vulnerable populations where they work, such as mines and garment factories, and where they seek care, such as maternal-child health clinics and general practitioners’ offices.195

Community-Based Care

The WHO recommends that “community-based care should always be considered before isolation or detention is contemplated. Countries and TB programmes should put in place services and support structures to ensure that community-based care is as widely available as possible.” 196 Community-based care can help reach vulnerable groups by reducing the costs associated economic and social costs associated with seeking continued access to care.197 Sacco et al. note that community-based care is generally the appropriate method of treatment for all forms of TB.198 For example, Lesotho has provided free, community-based treatment for TB since 1991. In 2007, PIH launched Lesotho’s first MDR-TB treatment program, using paid, trained community health workers to help deliver medication, support, counseling to families, and accompaniment to hospitals for very ill patients. This program is coupled with the training of “expert patients” to act as role models, the refurbishing the national TB laboratory, and the converting a former leprosy clinic into a new MDR-TB hospital.199 The effectiveness of community-based models has also been demonstrated in Latvia, Estonia, Georgia, Peru, the Philippines, Nepal, and the Russian Federation.200

Health Literacy and Reduction of Stigma and Discrimination

Reducing the stigma and discrimination associated with TB are an essential component of reducing vulnerability to the disease. This has been widely documented as effective with respect to similarly stigmatized diseases which implicate people’s human rights, including HIV. Examples of relevant efforts include education and outreach to improve health literacy about the disease and prevention and training health care workers and providers about “non-discrimination, informed consent, confidentiality and duty to treat”.201 Other measures include legal and policy reform to eliminate all forms of discrimination against people living with and affected by TB.

Empowering Patients and Communities

The empowerment of the most vulnerable groups is a priority, including women and children. This requires the participation, engagement and mobilization of the entire community. The Global Fund notes that “Patients and communities play an integral role in TB treatment literacy, social support, advocacy, communication and social mobilization. TB cannot be adequately addressed without meaningfully involving those most affected in the planning and implementation of policies and programs that impact them.”202

Social Protection

Income-Generating Activities

Interventions that reduce poverty and malnutrition among vulnerability and marginalized populations can help to reduce their high TB burden. A number of social protection interventions have been shown to improve health, education and nutrition in different settings in Latin America and South Africa. Examples include direct transfers of food or money to vulnerable households and increased access to microfinancing opportunities. Sometimes these schemes have been conditioned on behavioral requirements related to improving the success of the intervention, or directly related to improving health, such as sending children to school, participating in health literacy trainings, or accessing health are. The benefits of such activities could include improving the socioeconomic circumstances of people affected by TB and reducing financial barriers to diagnosis, treatment and care.203

Urban Regeneration

Many of the factors which increase vulnerability to TB at both the individual and population level are associated with urbanization—substandard housing, overcrowding, economic and legal insecurity and inadequate health facilities. Urban regeneration and slum upgrading schemes could reduce vulnerability to TB by directly affecting the physical environments in which people experience disease as well as increasing living standards by ensuring access to health services, schools and employment.204

Legal Assistance and Advocacy

Legal Assistance

Legal assistance can assist people affected by TB claim their economic, social, cultural, political and civil rights. Providing patients with representation can help them access care, combat discrimination and challenge measures which unjustifiably restrict their substantive and due process rights to liberty and freedom of movement. For example, recent litigation in South Africa’s Constitutional Court has successfully held prison authorities accountable for failure to prevent and treat TB in prisons. This work was supported by Section 27, the former AIDS Law Project, and is a successful example of legal advocacy to promote and enforce the rights of TB patients under constitutional law and human rights principles. For more information, see below: “Example 5: Litigating for prisoners exposed to TB in South African prisons.”205

Criminal Justice Reform

Reforming the criminal justice system can be a cost-effective method of reducing TB and HIV transmission, given its role in fueling the spread of TB. Poor resourcing and management of prisons, and poor judicial and correctional processing of individuals, contribute to overcrowding and substandard conditions. According to Todrys and Amon, examples of reform include reducing arbitrary pretrial detention, large-scale prisoner releases, reforming bail guidelines, expanding community service and parole programs, increasing judges, and improving access to legal representation.206 Moreover, the severity of law enforcement does not meaningfully reduce the prevalence of drug use and fuels the HIV and TB epidemics.207 Criminalization deters drug users from seeking prevention and care services and pushes them into environments where the risk of infectious disease transmission and other harms are increased.208 Drug policy that results in criminalization, arbitrary detention, and over-incarceration of drug users needs to be reoriented to consider its health and rights implications.

Health Systems Strengthening

Strengthening the facilities and systems in which people access health services is an essential component of the response to TB control. As the Global Fund notes, “Poor quality of care hampers global TB control efforts. Inadequate training and supervision of health workers, inconsistent drug supplies, inadequate diagnostic tests and limited resources inhibit early detection and appropriate treatment resulting in increased transmission and poor health outcomes. By tailoring services to meet the needs of patients and communities, a human rights focus will improve service delivery, ensure that resources used match community priorities and provide evidence that can be used to mobilize additional resources.”209 Relevant aspects of the health care system to be strengthened include health policy and regulation, mobilization and allocation of financial and human resources, improved laboratory capacity for diagnosis and detection of drug sensitivity, management and delivery of health services, management of medicines and medical technology, and data and information management.210

Notes

1 Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Questions and Answers about Tuberculosis (2012). www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/faqs/pdfs/qa.pdf.

2 See High Court of South Africa, Dudley Lee v. the Minister of Correctional Services, Case No. 1041. www.saflii.org/za/cases/ZAWCHC/2011/13.pdf.

3 See UCLA School of Public Health, “Susceptibility Definition.” www.ph.ucla.edu/epi/bioter/anthapha_def_a.html.

4 Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Questions and Answers about Tuberculosis (2012). www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/faqs/pdfs/qa.pdf.

5 Tiemersma EW et al., “Natural History of Tuberculosis: Duration and Fatality of Untreated Pulmonary Tuberculosis in HIV Negative Patients: A Systematic Review,” PLoS Medicine 6, no. 4 (2011). www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0017601.

6 Zaki SA, “Extrapulmonary tuberculosis and HIV,” Lung India, 28, no. 1, Letters to the Editor (Jan-Mar. 2011). www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3099522; Walls T and Shingadia D, “Global epidemiology of paediatric tuberculosis,” Journal of Infection 48, no. 1 (2004). www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S016344530300121X.

7 World Health Organization (WHO), Global Tuberculosis Control 2011 (2011). http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/2010/en/.

8 Global Health Education, “TB Tests”. www.tbfacts.org/tb-tests.html. Emphasis added.

9 Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Tuberculosis: General Information, Fact Sheet (2011). www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/factsheets/general/tb.pdf.

10 Global Health Education, “TB Tests”. www.tbfacts.org/tb-tests.html.

11 High Court of South Africa, Dudley Lee v. the Minister of Correctional Services, Case No. 1041.

12 Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Questions and Answers about Tuberculosis (2012). www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/faqs/pdfs/qa.pdf.

13 Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Tuberculosis: General Information, Fact Sheet (Oct 2011). www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/factsheets/general/tb.pdf

14 Diagram adapted from Parrish NM, Dick JD and Bishai WR, “Mechanisms of latency in Mycobacterium tuberculosis”, Trends in Microbiology 6, no. 3 (1998): 107-112. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0966-842X(98)01216-5

15 World Health Organization (WHO), Guidelines for social mobilization. A human rights approach to TB (2001). www.who.int/hhr/information/A%20Human%20Rights%20Approach%20to%20Tuberculosis.pdf

16 WHO, Tuberculosis, Fact sheet no. 104 (2013). www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs104.

17 Global Health Education, “TB Tests”. www.tbfacts.org/tb-tests.html.

18 WHO, Global Tuberculosis Report (2012). http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/75938/1/9789241564502_eng.pdf.

19 UN General Assembly, Report of the Special Rapporteur in the field of cultural rights: the right to enjoy the benefits of scientific progress and its applications, A/ HRC/20/26 (May 14, 2012). www.ohchr.org/Documents/HRBodies/HRCouncil/RegularSession/Session20/A-HRC-20-26_en.pdf.

20 WHO, Global Tuberculosis Report (2012). http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/75938/1/9789241564502_eng.pdf.

21 WHO, Tuberculosis, Fact sheet no. 104 (2013). www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs104; WHO, “10 Facts about Tuberculosis.” www.who.int/features/factfiles/tb_facts/en/index.html.

22 WHO, Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) 2013 Update (2013). www.who.int/tb/challenges/mdr/MDR_TB_FactSheet.pdf

23 WHO, Towards universal access to diagnosis and treatment of multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis by 2015, Progress Report (2011). http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2011/9789241501330_eng.pdf

24 WHO, Tuberculosis, Fact sheet no. 104 (2013). www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs104.

25 WHO, Global Tuberculosis Control 2011 (2011). http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/2010/en/.

26 WHO, Towards universal access to diagnosis and treatment of multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis by 2015, Progress Report (2011). http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2011/9789241501330_eng.pdf

27 WHO “TB diagnostics and laboratory strengthening.” www.who.int/tb/laboratory/

28 WHO Expert Group Meeting, Policy guidance on TB drug susceptibility testing (DST) and second-line drugs (SLD) (Geneva, July 23, 2007). http://www.who.int/tb/features_archive/xdr_mdr_policy_guidance/en/.

29 Dalton T et al., “Prevalence of and risk factors for resistance to second-line drugs in people with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in eight countries: a prospective cohort study,” Lancet 380 (2012). http://press.thelancet.com/TB.pdf

30 HIV stands for human immunodeficiency virus. AIDS stands for acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, which is an advanced stage of HIV defined by the demonstration of certain symptoms, infections and cancers. WHO, HIV/AIDS: Fact Sheet No. 360, Fact Sheet (Nov. 2012). www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs360/en/index.html.

31 TB Alert, “TB & HIV.” http://www.tbalert.org/index.php/about-tuberculosis/global-tb-challenges/tb-hiv.

32 WHO, Global Tuberculosis Control 2011 (2011): 1, 83; WHO, TB-HIV Facts 2011-2012. www.who.int/tb/publications/TBHIV_Facts_for_2011.pdf.

33 Pawlowski A et al., “Tuberculosis and HIV Co-Infection,” PLoS Pathogens 8, no. 2 (2012). www.plospathogens.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.ppat.1002464#s1.

34 Ibid.

35 Lonnroth et al., “Tuberculosis: the role of risk factors and social determinants,” in Blas and Kurup, eds., Equity, social determinants and public health programmes (2011): 219-241. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241563970_eng.pdf.

36 Andrews JR, “Multidrug-Resistant and Extensively Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis: Implications for the HIV Epidemic and Antiretroviral Therapy Rollout in South Africa,” The Journal of Infectious Diseases 196, suppl. 3 (2007). http://jid.oxfordjournals.org/content/196/Supplement_3/S482.long,

37 Ibid.

38 Ibid.

39 Pawlowski A et al., “Tuberculosis and HIV Co-Infection,” PLoS Pathogens 8, no. 2 (2012). www.plospathogens.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.ppat.1002464#s1.

40 TB Alert, “TB & HIV.” http://www.tbalert.org/index.php/about-tuberculosis/global-tb-challenges/tb-hiv.

41 WHO, HIV/AIDS: Fact Sheet No. 360, Fact Sheet (Nov. 2012). www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs360/en/index.html.

42 WHO, Fight AIDS, fight TB, fight now: TB/HIV information pack (2004). www.stoptb.org/assets/documents/resources/publications/acsm/InfoPackEnglish.pdf

43 Andrews JR et al., “Multidrug-Resistant and Extensively Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis: Implications for the HIV Epidemic and Antiretroviral Therapy Rollout in South Africa,” Journal of Infectious Diseases 196, Suppl. 3 (2007). http://jid.oxfordjournals.org/content/196/Supplement_3/S482.long,

44 WHO, WHO policy on collaborative TB/HIV activities: Guidelines for national programmes and other stakeholders (2012). http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2012/9789241503006_eng.pdf

45 Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, US Global Health Policy Fact Sheet: The Global HIV/AIDS Epidemic, Fact Sheet (Dec. 2012). www.kff.org/hivaids/upload/3030-17.pdf.

46 WHO, Tuberculosis Global Facts 2011-2012. www.who.int/tb/publications/2011/factsheet_tb_2011.pdf.